Once And For All, What Makes an Outlaw?

Today is the 4th of July: the birthday of The United States. It is also arguably the birthday of the Outlaw movement in country music.

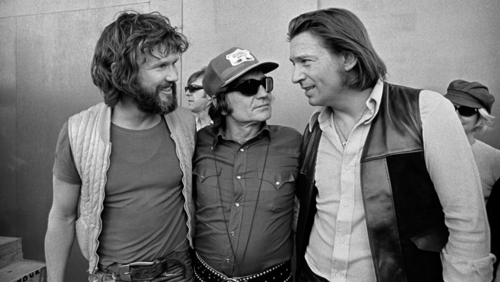

Nailing down an exact date when the Outlaw movement started depends on who you talk to, but a popular one is when Willie Nelson’s legendary 4th of July Picnics started in 1973. The Dripping Springs Reunion happened the previous year, but this was held in the Spring, and was marked by classic country performances from people like Bill Monroe, Loretta Lynn, and Roy Acuff. 1973 is when native Texans Willie, Waylon Jennings, and Kris Kristofferson famously reunited to headline the festival.

There’s been a lot of questions on what really makes a country music Outlaw, and misconceptions abound. That is why the original Outlaws hated the term, and why new artists as well as fans use the term incorrectly. So I thought I would clarify:

Being a country music Outlaw has nothing to do with having tattoos. It has nothing to do with motorcycles, or how much you cuss in your music or reference drugs. It has nothing to do with rock influences in your music, nothing to do with if you “party” a lot or live an “Outlaw” lifestyle. Being an Outlaw has very little to do with the music itself. You can play traditional country, neo-traditional country, country-rock. There is no definable Outlaw country sound. As long as it is country music, it can be Outlaw music.

“Outlaw” is a business term more than anything. Yes, all the above can be and have been elements of the overall Outlaw culture, but neither Willie, Waylon, or Kris had tattoos, rode motorcycles, and none of them were big drinkers. What they had in common with Outlaws that were big drinkers like Johnny Paycheck, or that rode motorcycles and had tattoos like David Allan Coe, was that they had all fought for creative control of their music from the country music establishment, and won it. That is what makes a country music artist an Outlaw.

And just for the record, Johnny Cash, Merle Haggard, and George Jones were never considered Outlaws, though you could say that Cash became an Outlaw near the end of his life with The Highwaymen project, and the Rick Ruben American Recordings later on, and he did have many dealings with The Outlaws over the years.

The original Outlaw was Bobby Bare, who was the first to fight for creative control of his music, and the first to open up new themes that before were taboo in country. This is typified by the 1966 song “Streets of Baltimore,” which very subtly is about a woman leaving her man to become a prostitute. The song was written by Tompall Glaser. Another taboo hurdle was cleared by Kris Kristofferson’s “Sunday Morning Coming Down,” which references wanting to be “stoned.” But Tompall started the Outlaw revolution in earnest when he built a renegade recording studio called “Hillbilly Central” on 19th Ave in Nashville.

At the time almost everything in Nashville was controlled by a few men: mainly RCA producer Chet Atkins, and the Acuff-Rose Publishing Company. Nearly all music coming out of Nashville was recorded at RCA’s “Studio B”. The songs recorded by artists were written by dedicated songwriters, and selected and arranged by record label producers. All studio musicians were selected by the producer, and were unionized so that no outside musicians (from an artist’s touring band, for example) could be used.

Enter not a musician, but a slick lawyer from New York named Neil Reshen. Reshen helped two disgruntled RCA artists—Willie Nelson and Waylon Jennings—break their RCA contracts and wrestle control of their music. (You can read more about Reshen HERE.) Willie and Waylon were inspired to do this by watching Bobby Bare and rock musicians receive almost unilateral control over their music. Willie left RCA, and eventually singed with Atlantic, a rock label, with complete creative control. Waylon stayed with RCA, but established control over his music the likes of which had never been seen before on Music Row.

The first thing Waylon did was record an album of Billy Joe Shaver songs in 1973 called Honky Tonk Heroes at Tompall’s Hillbilly Central. This was one of the most significant moves in country music history, because after Reshen’s legal maneuverings, it broke the back of the Music Row monopoly, and opened the floodgate for artists to be able to record their music outside of RCA’s “Studio B” (or Studio A) and without using union studio musicians. It also ushered in a period where label-owned studios became virtually extinct, and independently-owned studios thrived.

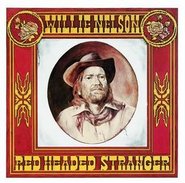

The next significant move was Willie Nelson releasing Red Headed Stranger in 1975—considered by many as the greatest country music album of all time. It was done in a small studio in Garland, TX with Willie’s own musicians on a shoestring budget. The next year RCA released Wanted! The Outlaws, which became the first million-selling album in country music history. All the songs on those two albums were recorded with the artists having the final say.

The next significant move was Willie Nelson releasing Red Headed Stranger in 1975—considered by many as the greatest country music album of all time. It was done in a small studio in Garland, TX with Willie’s own musicians on a shoestring budget. The next year RCA released Wanted! The Outlaws, which became the first million-selling album in country music history. All the songs on those two albums were recorded with the artists having the final say.

So when artists like Josh Thompson say to blame their Outlaw ways on Waylon, meaning his college-style coed drinking antics and pop-style “partying,” it’s fair to object. Waylon’s “Outlaw Ways” would be to insist on not putting out music that was tooled from beginning to end by industry producers. It’s also fair to object when someone thinks being an Outlaw means getting a skull tattoo and interjecting devil and drug references into their music.

“Outlaw” is a state of mind; an approach based on strong-willed principles. Anything beyond that is lesser qualifying points based on opinion or simple elements of culture.

July 4, 2010 @ 12:29 pm

Nice article man, happy 4th everyone

July 4, 2010 @ 4:19 pm

Well said! I have had a hard time defining what this “outlaw” movement is. It’s kinda like the definition given by the Supreme Court for porn, “I know it when I see it.” I’ve always gone by that mantra for music. I know it when I hear it. You give a good historical reason for what makes an outlaw…it’s fighting against a status quo, broken system.

Hellbound Glory opened up for Eric Church a couple weeks back at The Knitting Factory and this dichotomy between “outlaw” and corporate Nashville was at its most stark. Hellbound blew the place up with genuine lyrics and hard hitting beats. No frills. While Eric Church sang through an auto-tuner, lighting guy, smoke machine, fireworks and sounded like a bad AC/DC cover band. I mean it was REALLY bad. I didn’t know enough not to like the guy before hand, so I actually gave him a fair shot. Just so phony and generic. Anyway, all that to say: Great article and Happy 4th of July!

July 4, 2010 @ 4:22 pm

Glad ya did this article as it did clear some things up for me. I had thought incorrectly, but hey…at least I know what country music should sound like. Anyhow have a Happy 4th of July America.

July 4, 2010 @ 5:40 pm

Happy 4th to you, Triggerman, outlaw of savingcountrymusic.com.

July 4, 2010 @ 6:18 pm

like waylon said don’t you think this outlaw bit has done got out of hand but great article very few people give credit to bobby bare

July 4, 2010 @ 7:26 pm

What is an Outlaw? It’s a bullshit term made up to sell records. Anyone considered an Outlaw just did shit there way. That to me means making honest music. Perhaps then what one calls Outlaw I call honest. The boys in Bakersfield were outlaws because they made their music their way. Bill Monroe was an Outlaw because he along with Flatt Scruggs and Chubby Wise created a whole new genre of music. Flatt and Scruggs were then double outlaws because they added a dobro. Hell Earl is a triple outlaw then for truly defining 3 finger from clawhammer. Jimmy Martin was an Outlaw because he played his brand of bluegrass Big N Country and he played his way no matter what. The Osbornes were Outlaws because they introduced electric instruments into bluegrass. I guess what I’m getting at is that if you do something your way you’re an “outlaw” because it’s honest music. Often times when you do it your way you add to the sound. What makes an honest musician is one who has their own distinct sound. Toby sounds like McGraw but Hank don’t sound like Tubb. I guess what makes someone an “Outlaw” is mainly comprises two things: you add to the sound and you do what’s in your heart no matter what the fuck anyone says. It has nothing to do with how many fuckin stupid songs you write about how much of a badass you are for consuming too much drink and drug. I look forward to the day when some of these younger guys get that through their head. Cause a lot of guys in this “underground scene” are just self proclaimed outlaws who play the most predictable stale crap that is full of the bad cliches. Don’t you think this outlaw bit’s done got out of hand? I know I do. But, what the fuck do I know?

July 5, 2010 @ 12:22 am

First off, I don’t really like the term ‘Outlaw’. But I understand it’s derivative.

UncleMary, you made a great point about Bakersville. Buck Owens told Nashville he knew how to make his records way before Willie or Waylon. ‘Live, From Carnegie Hall’ is one of my favorites.

Anyways, we all need thank Triggerman for his great writing abilities and research. Thank you sir, this site helps the day a little easier!

July 5, 2010 @ 3:28 am

i wonder how many music row people read your articles… this one is another slap in their faces.

July 5, 2010 @ 3:53 pm

I mostly use the term “outlaw country” to differentiate from pop country, but lately I’ve been saying “underground country” instead. May the outlaws rise again. Nice article Triggerman.

July 6, 2010 @ 1:29 am

Very insightful as always Triggerman.

You and others may or may not agree, but I would

like to add some requirements to this.

Outlaw is short for “outside the law.”

So I would have to say breaking some laws every now and

then helps.

July 6, 2010 @ 6:10 am

Triggerman, if simply fighting the system (Nashville) for the sake of your art and creative freedom, makes someone an outlaw. You’re leaving it open for Toby Keith, Trace Adkins, Gretchen Wilson, Big N Rich, Cowboy Troy, Leanne Rhymes etc , to be considered outlaws. They all fought for lyrics and or other freedoms in their music, however bad their ideas sucked.——— If Taylor Swift fights with her label, because she wants to sing a cover of the “Barney The Dinosaur” song on her next record, will you welcome her with open arms too?

July 6, 2010 @ 6:11 am

My name says it all.

July 6, 2010 @ 8:05 am

FOR ONE THING OUTLAW IS A WORD AND IS NOT OWNED BY ANY ONE PERSON BUT TRY TELLING THAT TO THE OUTLAWS MOTORCYCLE CLUB..THERE WAS A GREAT BAND CALLED THE OUTLAWS LED BY THE LATE GREAT HUGHIE THOMASON WHO HAD T-SHIRTS,STICKERS,ETC. BUT OUTLAWS M/C THOUGHT THEY OWNED THE WORD OUTLAW..IF YOU HAD ANYTHING ON WITH OUTLAW ON IT THEY REFERENCED IT TO THEM AND STILL DO..YOU ALSO CAN’T WEAR ANYTHING WITH A CITY NAME ON IT THAT MIGHT REFERENCE THE HELLS ANGELS SUCH AS THE CITY OF WINSTON SALEM NC WHERE SOME H.A’S ARE FROM..THE WORD IS DEFINED AS AN HABITUAL CRIMINAL EXCLUDED FROM THE BENEFITS AND PROTECTION OF THE LAW WHICH DOES NOT DEFINE WAYLON JENNINGS OR SOME OF THE OTHER FORMENTIONED PEOPLE IN YOUR ARTICLE BUT DID A FEW ALTHOUGH WAYLON DID INDULGE IN SOME UNLAWFUL DRUGS..HE WAS CHARGED WITH POSSESION OF SOMETHING THAT WAS LONG GONE..DON’T YOU THINK THIS OUTLAW BITS DONE GOT OUT OF HAND???JUST A LITTLE INFO FROM ANOTHER SIDE OF THE WORD OUTLAW!!!

July 6, 2010 @ 8:48 am

Pillsbury,

That’s a good point. I am not saying that there aren’t other factors in deciding what an Outlaw is. What I’m saying is that it all has to start with fighting against the system. For example: Toby Keith broke out of Music Row to start his own label and create creative control for himself, or at least, that was the story. So did Gretchen Wilson. But really their motivation was to get their hands on more of the pie. You can tell that clearly by listening to the music. Their music is still within the system, played on top 40 country radio, videos on CMT. They’re not more out of the system than Taylor Swift is.

Eric Church and Josh Thompson, or more specifically the marketeers behind their identity, cannot claim that they are Outlaws because they ARE working inside the system, even though they may have songs that talk about how tough they are, or that they drink a lot and use drugs.

I can’t keep up with who is claiming they are Outlaws or not. I don’t know if Toby Keith is. But these “New Outlaws” are without question all working from the same formula, the same playbook of how to exploit demographics of people who do not identify with the current polished Nashville sound.

Some Eric Church and Josh Thompson fans have pointed out fairly that these two guys don’t call themselves “Outlaws,” yet they talk about them all the time in their songs, have anti-Nashville songs, talk tough from their misguided ideas of what an Outlaw really is, and are commonly referred to as the “New Outlaws” by industry and media types.

Don’t know if I’m helping at all. The main point I was trying to make here is that someone cannot claim to be an Outlaw just because they drink whiskey. Its much deeper than that.

July 6, 2010 @ 8:51 am

Pete,

I don’t know if I’d agree. “The Outlaws” was a term created to say they were working “Outside of the law of Nashville.” In fact I think your interpretation is what Waylon was rebelling against in “Outlaw Bit.”

Everybody has done something illegal at some point. Again, not saying that “Outlaw” behavior is completely irrelevant, but what first must be there is fighting against the country music establishment.

July 6, 2010 @ 11:13 am

Triggerman, Would you consider the likes of BR549 and Dale Watson outlaws then? They’re outside the system, but not fighting it either. They more or less coexist with it.

——– On a side note, would you fuck Taylor Swift, if given the chance?

July 6, 2010 @ 12:43 pm

I wouldn’t say Dale Watson is within the system at all, I think he’s purposely outside of it, signed to a indie label, writing songs like “Nashville Rash” and “That’s Country My Ass.” He’s definitely an Outlaw, though he prefers the worst name ever given to any form of country “Ameripolitan.”

Sounds like something I’d order in a cake cup w/ sprinkles.

BR549 was more working within the system, because they were signed to a major Nashville label, and were given a little attention by the charts and radio. I think BR549 more led by example so to speak, not speaking out so much as just making great music and proving you didn’t have to sell out to do so.

Hate hypotheticals, but I would have sex with Taylor Swift. But only because as The Triggerman, I have a super human ability to be able to delineate sexual activity from my emotions, thoughts, and principles, and Taylor Swift is an undeniable hot.

July 6, 2010 @ 2:22 pm

I think the cover of Dale Watson’s “From the Cradle to the Grave” answers the question of whether or not he’s an “outlaw”. Read the headstone he’s standing next to: “R.I.P. Country Music”.

Thanks for everything Dale!

July 6, 2010 @ 5:54 pm

Triggerman,

I love you as a brother.

Everything you do is is extremely relevant

and for a magnificent and noble purpose.

And as someone who has battled in the cowpunk trenches

since 1979, I venture to your page frequently, and

read as much as I can with extreme relish.

However, that said, I must say I think you have

crossed the line. I know you are a man, and I can

understand your logic as I am the last one to pass judgement being the heathan that I am.

But I must hereby state, that I wouldn’t fuck Taylor Swift

with your dick.

July 6, 2010 @ 7:09 pm

HEHEH Pete.

Honestly, the whole would’ya/wouldn’ya about Taylor deserves way more treatment than a passing thought to satisfy a passing question at the dying end of a comment thread.

I might broach the subject in full here very soon.

July 8, 2010 @ 10:29 pm

GREAT INFO! “OUTLAW MUSIC” is going against the grain of what is considered acceptable by the mainstream and sticking with it against popular critisism…JUST because you love what you are doing.

July 8, 2010 @ 11:36 pm

That’s an excellent, excellent article. I agree with you… to make a list to determine whether you’re an “Outlaw” or not defeats the purpose. Once you start doing that, then you’re ultimately NOT an “Outlaw” because you’re looking for proof that God exists.

I don’t know what the greatest country music record ever is, but Red Headed Stranger has got to be in the running.

Excellent article.

July 10, 2010 @ 11:45 pm

Very well-put article. Nice mentioning the Waylon album with Billy Joe’s masterful writing, but if it weren’t for guys like Mr. Shaver and Townes Van Zandt, to name a couple, the outlaw movement would never have existed.

July 13, 2010 @ 6:57 am

I only hear/see one guy currently that could walk into the “honky tonk of fame” and not be laughed at by the legends like Waylon, Willie, Bobby Bare, etc…

Jamey Johnson.

Came into Nashville trying to get a deal, played by the rules, got shelved, and then put out “That Lonesome Song” which clearly is not cut by record execs.

Also, might wanna check out a band by the name of Whitey Morgan and the 78’s. They aren’t proclaiming to be “outlaws” but simply say “we aren’t re-inventing the wheel, just getting it rolling again.”

I don’t care if Eric Church gets label support and wears the “black hat” as an outlaw if that gets more radio play for guys like Jamey Johnson, Whitey Morgan, etc…

July 16, 2010 @ 1:12 pm

Triggerman,

Be ready, the new country crap is gonna get a whole lot worse. when Carrie underwood does songs like “undo it” I can only hope this garbage is a short lived, really bad trend. When the CMA awards praises her with awards i think fat chance. You know damn well that now this type of music “id call it country if it even remotely was” will be pushed as the standard. You know how it works. “It worked for her, lets try it with some others too.”

I live in the middle of wisconsin. We have a pretty good mix of radio stations. The main one is a pop station teens listen to. The country stations are modern country and a classic country station. THANK GOD! The modern country station loves josh thonpson, carrie underwood,and so on. Its so modern there are times there is no difference between it and the pop station. And every week it moves more in that direction. A country version of motley crue’s home sweet home? Really?! When George Jones made his comments about stealing country’s identity, listen to this station and you’ll know exactly what that means.

I think outlaws are a once in lifetime thing. But i also think they come out when they are desperately needed. Waylon realy hit when lounge country seemed to be the norm.If that trend repeats, i cant wait for the true, new breed of outlaws. And i’m sorry, Josh Thompson is not one of them.

August 3, 2010 @ 7:18 am

Kent,

9/14/10 Jamey Johnson double album. That’s your new breed!

Black Vest – Badge of the Outlaw « Saving Country Music

September 9, 2010 @ 10:17 am

[…] readers here already know that what makes a country music Outlaw is not image, quite the contrary. It is an independent spirit that is unwilling to bend to popular […]

Jim Marshall Photography LLC: The Official Blog

August 25, 2011 @ 1:13 pm

[…] a blog entry on savingcountrymusic.com, someone with the moniker “triggerman” makes the case for how this 1973 coming together […]

August 29, 2011 @ 11:05 pm

Wow, that was a well written entry Triggerman!

As a music journalist, I deal with a multitude of genres, but I have always loved true country music. I was skeptical of the whole New Outlaw movement initially, but after a lot of thought I realized that it was essentially meaningless because as you outline above the true outlaws never labelled themselves as such. It was about their actions & convictions, not their dress code.

I think that outlaw country is similar to punk music in that the originators only sought to put out their ART by their own rules, against the colossal odds imposed by the mainstream. Today there are bands like Green Day & even their copycats who dub themselves as punk bands as part of a marketing gimmick.

While a lot of people have a true hatred for Hank 3, I think that his choice to release albums that incorporate classic country, rockabilly, garage punk, thrash metal and even cattle calls makes him seem like a likely bearer of the outlaw label. But then again, now that he has won his artistic freedom, he would be the first to wave a middle finger at those looking to confine him in a box with a label. That being said, I am always open to new music and I love discovering something that surprises me. As an avid Waylon fan, I can honestly say that the last thing I want to hear is a copycat. As much as I loved what he did, he already did it. That is why I love the idea of Outlaws. I like to hear guys who bend the boundaries or take something that already exists to the next level. Sure there have been gypsies making music since they first left India, but Gogol Bordello took it to the next creative level. The Clash mixed garage rock, punk and reggae to create something new. The innovators are the true PUNKS, the true OUTLAWS. The only argument that I have is the idea that Outlaw only relates to country music. I think that is exactly NOT what outlaw means. When Shooter takes his country roots, blends it with southern rock, left wing politics, Stephen King & Pink Floyd styled psych rock… now that is Outlaw, but I shake my head every time I see Black Ribbons in the Country section at the record store.

Anyway, thanks for the great article. I enjoyed reading it.

August 9, 2012 @ 12:47 pm

This history lesson oughta be required reading I’m Nashville.

August 9, 2012 @ 12:50 pm

*in

August 13, 2012 @ 10:08 am

Triggerman,

I admit I’m a big Eric Church fan, but I do see your point when it comes to being a tried and true ‘Outlaw’ in the country music business and why that eliminates nearly every wannabe out there. But I can’t help but think you lump EC into the ‘phony’ category because you simply don’t like the guy, as many of your rants and posts on here would attest.

I don’t think there’s anybody making music like EC is in Nashville. Now, I know that doesn’t mean much for somebody who devotes himself to the underground world of country music, which I admit I’m pretty naive too, but its true. Smoke a Little Smoke is a song unlike any I’ve ever heard on the radio and is a song Church had to fight for in order to be released. He was told it would be career suicide by the corporate suits, yet he stuck up for the song, knew his audience and wouldn’t take no for an answer. It went on to be his biggest hit at the time and it spawned his platinum selling album ‘Chief’—which was given a favorable review by none other than you yourself for being bold and refreshing from a mainstream point of view.

From Sinners Like Me to Chief his stance, his views and the overall feel of his music has never changed. He knows who he is and to this point has never wavered. He came off brash at the beginning getting kicked off the Rascal Flatts tour and with songs like ‘Lotta Boot Left to Fill’ but looking back, that was just him telling it how it is from his point of view. This, while he was still a ‘B’ or ‘C’ list performer playing at dive bars in front of 200 people. Now he’s selling out arena’s with the exact same bravado. A testament to him sticking to his guns, keeping it about the music and providing his fans everything they want and more.

Now keep in mind this is just me presenting a case for Eric Church, I’m not criticizing you or this site. You’re a very talented writer with a deep knowledge of country music and I love this site. But I think you are too damn hard on Eric Church just because you think he’s arrogant and he’s mainstream. Maybe your point is that you can’t be an Outlaw if you’re mainstream. But if there’s a mainstream artist who most closely resembles one, its Eric Church.

August 13, 2012 @ 11:21 am

i need a shot in the arm for the old career so i would like you guys permission to jump on the outlaw bandwagon if i could. would it be okay to refer to myself as an outlaw if i: did cocaine with waylon, got real real drunk with jerry lee lewis and george jones and hank jr at possum hollar one night, smoked pot with willie, gigged with david allen coe, dated sammie smith, played for the hells angels, the banditos and the scorpions at a bike meet when they were gonna divide up the texas drug market (they couldn’t agree, fought and roared off in different directions as we were playing communication breakdown (ironic, huh?), possess a coricidin bottle that belonged to gary stewart, watched jerry jeff walker bust to pieces one of my favorite guitars, got screwed by reprise records and sustain records (rounder was good to me), wrote a song that brought the hippies and the rednecks together (and appears unable to die), got a co write with lloyd banks of g unit and..and..uh..some other stuff but i can’t remember. i’ll buy some aviator sunglasses if need be. thanks for your consideration. rwh

August 13, 2012 @ 3:06 pm

God Bless You Ray Wylie Hubbard!!!

August 13, 2012 @ 10:05 pm

It just occurred to me that the term “Outlaw” is much like Studebaker. They don’t make em any more. It was an era that cannot be reproduced. God give strength to the likes of Merle Haggard and Billy Don Burns, among the last true outlaws standing.

August 14, 2012 @ 8:39 am

I thought Honky Tonk Heroes was recorded at RCA? And I would definitely say This Time was a more significant album for Nashville and artists like Waylon.

August 15, 2012 @ 12:49 pm

Hey Ray! If ya wana get yer outlaw on … We would love to have ya come be a guest on free radio KAOS here in Austin , Texas! We love yer music ! Come help us stick it to the man …outlaw radio style !

January 8, 2013 @ 9:54 am

That’ll sum it up for me! As a upcoming artist an article like this truly inspires! Outlaw by definition is nonconformist ; it has nothing to do with drinking or drugs so as an artist and writer I wondered if I was I’ll never be Waylon or Willie or Johnny or Kris and Hank and the list goes on… but I hope I at least make um proud in a sense to represent my ideas my creative penny to contribute to thoughts of people then I guess to turn the tide from the opinion of my mentors I’ll leave you with this spin on one of the greatest lyrics of all time “my heros have always been outlaws ” they would be pissed I called um that but ironically enough that’s just exactly what an outlaw is…. thanks for inspiring me we”ll see you down the road!

September 19, 2013 @ 3:32 pm

Thanks for the great historical insights.

August 13, 2017 @ 3:42 am

Extremely well-put article. Pleasant saying the Waylon collection with Billy Joe’s magnificent written work, yet in the event that it weren’t for folks like Mr. Shaver and Townes Van Zandt, to name a couple, the criminal development could never have existed.