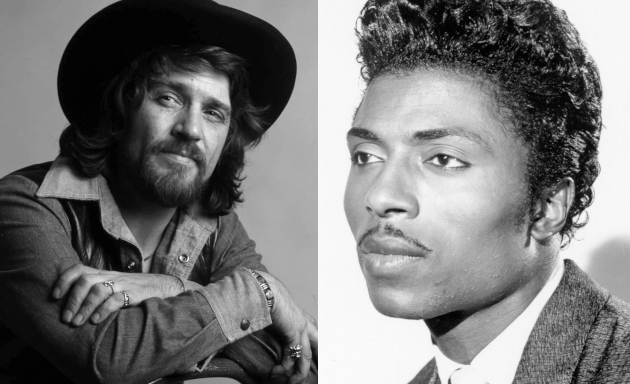

The Time Waylon Jennings Got Fired For Playing Little Richard (RIP)

Those that know Waylon Jennings know that one of the primary contributions he brought to country music was importing a little bit of across-the-tracks rock ‘n’ roll influence into the genre. Unlike many modern country performers, Waylon did it with a respect for the original roots of country music, but he undoubtedly did it.

Though criticized himself in his time for being too rock and roll, Waylon satisfied many of those concerns every time he opened his mouth and sang in that inescapable West Texas drawl. He later brought the legendary steel guitar player Ralph Mooney out on the road with him to underscore his country sound. But the hard-pounding bass drum in synchronous rhythm with the bass guitar was something that hadn’t been implemented in country music before.

You can’t hardly blame Waylon for bringing a little rock ‘n’ roll to country since he came up playing bass in Buddy Holly’s band. As some may know (and others may not), Waylon was supposed to be on that fateful plane ride in 1959 that took the life of Buddy Holly and resulted in the legend of “The Day The Music Died,” but Waylon gave his seat up to The Big Bopper.

Waylon also lost his first real job for playing Little Richard. Radio station KVOW AM 1490 in Waylon’s hometown of Littlefield, Texas (located just north of Lubbock) hired Waylon on as a teenager and aspiring musician, and by 1956, he was the voice of the station. Along with ample amounts of country music, and even performing live on-air when he had the opportunity, Waylon would play a little rock ‘n’ roll too.

In his autobiography Waylon (cir. 1996), the country legend explains how Littlefield and Lubbock weren’t segregated like certain parts of the South and Texas, but it was seriously frowned upon for the white and black populations to intersect. Waylon recalled asking his daddy, “What if they mixed black music with the white music? Country music and blues?” His dad replied, “That might be something,” and went back to pulling transmissions.

Waylon also recalled sneaking to the black side of town to hear the blues and early rock bands play. He also would play African American performers on Littlefield’s KVOW, 1490.

“On my radio show we’d do some of the rock ‘n’ roll things: Chuck Berry, Ray Charles, Little Richard. Every time I played a Little Richard record the owner would come all the way back to the station from home. He wouldn’t even call. He’d just cuss me, until one night I played two of them in a row and he fired me.”

Later in Waylon’s career, it would be his long-time drummer Richie Albright who would suggest to a frustrated Waylon who was tired of being under the oppressive thumb of producer Chet Atkins, “There’s another way of doing things, and that is rock ‘n’ roll.” Richie Albright didn’t only mean adding his now signature pounding bass drum to the mix, it also meant taking cues from rock artists who had won the creative freedom to write and perform their own songs. Soon, the Outlaw era in country music was born.

It was Richie Albright who made the suggestion. But it was artists like Little Richard who inspired the move. Little Richard was one of the origination points for the raw abandon that would turn rock ‘n’ roll into a revolutionary influence in society, rattling cages, breaking down barriers, and rewriting norms. He was cool before we knew what cool was. And as the station manager for KVOW, AM 1490, Littlefield, TX found out, you can’t hold that level of coolness back forever. You also can’t tell Waylon Arnold Watasha Jennings what to do.

In 1983, Waylon covered Little Richard’s song “Lucille” as “Lucille (Why Won’t You Do Your Daddy’s Will)” for his album It’s Only Rock and Roll. The song went to #1.

There are some people who say I use too heavy of a beat and too many instruments…but if instruments and beats made our music then we’d be in trouble anyway. The soul of the music is in the singer and I don’t believe anybody can really sing country as well as the old boy who’s lived it. Country music is like black man’s blues. They are only a beat apart. It’s the same man, singing the same song, about the same problems, and his loves, his losses, the good and the bad times.

–Waylon Jennings

May 9, 2020 @ 10:19 am

Very interesting, never heard that Waylon getting fired story. If Little Richard comes on and you don’t start moving you better check your pulse! RIP to a pioneer.

May 9, 2020 @ 11:03 am

RIP one of the true founding fathers. Hope his legacy will live on.

May 9, 2020 @ 1:12 pm

Of all the original rock & rollers, my favorites have always been the wild piano boogie guys like Little Richard and Jerry Lee Lewis. Little Richard was a force to be reckoned and truly an odd ball for the time. Whereas Chuck Berry (no offense, he was great too) was trying to sound as vocally “white” as he could to fool radio listeners (smart, but still), Little Richard was an unapologetically wild, black, queer, eye-liner wearin’, peacock struttin’ mofo from day one. Man had style and attitude. He embodied the true original spirit of rock & roll. RIP.

May 24, 2020 @ 5:20 am

No offense BUT Chuck Berry was simply sounding like Chuck Berry! What in the H does “sounding white” mean any way? Rural, city, suburban, Tennessee, NewYork, European?! Ever heard the man speak? I don’t ever recall him sounding like anybody BUT Chuck Berry.

May 24, 2020 @ 10:00 am

At the risk of getting baited down a rabbit hole here, let’s not be obtuse. You don’t need to be a professional linguist to acknowledge that modes of speech, dialect, accent, cadence, tone, and slang have historically varied in America by race, especially in vocal music, and those modes have been subject to appropriation and mimicry between groups. Mind you, I don’t abide by the notion that “appropriation” between cultures and races is a malicious phenomenon, rather a natural, organic, and even a positive and necessary one.

Now listen to the various forms of “hillbilly” (ie. white) and “race” (is. black) music of the 30’s, 40’s, and early ‘50’s. You’re going to hear distinct differences in the vocals between genres. In the mid to late 50’s however, with rock & roll, those vocals styles started blending, but black artists tended to retain the vocal styles and intonations of gospel and blues music, while white artists tended to retained the vocal styles and intonations of “hillbilly” music (hence the term “rockabilly”) otherwise they mimicked various qualities of black music (a more common trend than the reverse, especially going into the 60’s with the Beatles and Stones etc.).

Now compare Chuck Berry’s vocal style to Little Richard’s. The former retains the clipped, nasal quality of most white vocalists of the time, while the latter retained the elastic, wailing quality of most black vocalists of the time (typical of black gospel/church singing). In other words, Chuck Berry shared more vocal traits with white vocalists than with black ones of that era.

Chuck Berry himself acknowledged the influence of hillbilly and country on his style, which was an odd, but marketable quirk. Not unlike Elvis being influenced by black gospel and blues being an odd, but (highly) marketable quirk.

It’s debatable whether Chuck Berry sang the way he did as a put-on to get some edge commercially, to fool white deejays into assuming he was a white artist, but it didn’t hurt and it’s not unheard of in the mid-century music business to hide the race of the vocalist when plugging to radio deejays until they’ve developed a solid foothold with their largest commercial base – white people. Charley Pride, anybody?

Anyway, I’m not impugning or slandering Chuck Berry. The man was justifiably a legend, a trailblazer, and one of my favorites, but to imply that Chuck Berry developed and existed in a vacuum, with no stylistically commonalities with other artists or vocalists, or to deny that there weren’t (aren’t) distinct differences in the vocal qualities of traditionally black or white genres of music (or speech), is comically naive.

May 24, 2020 @ 5:29 pm

Your response short or long at its heart isn’t one unexpected.

May 9, 2020 @ 3:42 pm

Those days were dam good music rip Waylon an the rest of them still listen to it all.

May 9, 2020 @ 4:25 pm

Good job Trigger. One story, 2 legends, in their respective fields!

May 9, 2020 @ 4:40 pm

Rip Little Richard, he was a dynamo! Waylon was too, may they both rest in piece, I’m sure they are jamming together now, along with a whole cast of others.

May 9, 2020 @ 5:01 pm

For me these types of articles are where your writing truly shines (American trilogy story, you never even called me by my name story). Thanks for the historical insights, it has been 20 years since I read that book and had forgotten this!

May 9, 2020 @ 7:01 pm

Great article.

May 9, 2020 @ 7:02 pm

Great read, Trig !!!

May 10, 2020 @ 7:08 am

Off topic as far as Waylon goes, but if you haven’t heard the Little Richard/James Gang song “But I Try” be sure to check it out. It’s got the James Gang in their prime with Little Richard on piano and vocals. It absolutely rocks. It was released on Joe Walsh’s last solo album.

Also, Trigger, maybe you could write up a review of Little Richard’s 70’s album “The Rill Thing”. Not exactly country, but its Muscle Shoals at least and he covers Hank Williams!

May 10, 2020 @ 5:58 pm

Cool. I’ll have to check that out.

May 10, 2020 @ 8:44 am

Captivating article about these two legends. Great reading!

May 11, 2020 @ 12:29 am

Even the greatest were influenced by the greatest. It’s articles like this and this kind of information about legends that keeps our minds – and ears – open. Excellent article, Trig.

May 14, 2020 @ 9:00 am

Trigger, Excellent article. Thank you!