‘The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down’ Needs No Redemption

“I have always thought ‘Dixie’ one of the best tunes I have ever heard.”

–Abraham Lincoln

The fear when efforts were undertaken to strike anything that in any way could be construed however indirectly as being sympathetic to the Confederacy out of the public record was the slippery slope presented that may ultimately result in important pieces of art being mischaracterized and ultimately cancelled under false pretenses. Well ladies and gentlemen, we have officially reached that point.

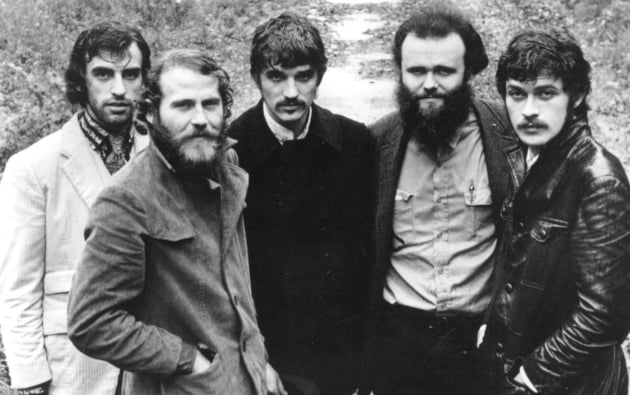

For over five years Saving Country Music has been using the song “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down” originally recorded by The Band as an example of how battling against Confederate references in art could go too far. Written by Canadian Robbie Robertson, sung by the universally-revered and outspoken progressive Levon Helm, and made into a pop hit in 1971 by folk singer and activist Joan Baez who took the song to #3 in the United States, “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down” is an iconic piece of Americana and music history.

Time named “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down” to their “All-Time 100 List of Greatest Songs.” It’s been enshrined in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame as one of the 500 songs the shaped the genre. Pitchfork called it the 41st best song of the 60’s, and Rolling Stone put it at #245 on their list of the “500 Greatest Songs of All Time.” Beyond The Band and Joan Baez, the song has been covered by countless artists, from Johnny Cash, to The Allman Brothers, to soul artist Dobie Gray, to the Jerry Garcia Band.

And throughout that legacy, nobody has ever questioned the ethics or message of the song because it in no way is glorifying the Confederacy. It is telling a story from the perspective of a poor Southerner at the end of The Civil War who “is in defeat.” But all of a sudden the song is being presented as problematic—as we knew it eventually would be—and bereft of critical details of the song’s writing and legacy for context.

The impetus for the discussion is when 26-year-old Easy Eye Sound-signed singer and songwriter Early James from Alabama performed a version of the song on a tribute to the movie The Last Waltz that chronicles The Band’s final concert. The tribute took place Monday, August 3rd, and was hosted by fellow Easy Eye Sound artist Marcus King. Selecting “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down” to play, Early James chose to change the original lyrics of the song to include strong anti-Confederate sentiments.

Unlike my father before me, who I will never understand

Unlike the others below me, who took a rebel stand

Depraved and powered to enslave

I think it’s time we laid hate in its grave

I swear by the mud below my feet

That monument won’t stand, no matter how much concrete

Early James changing the lyrics is not really where the issue arises. No different than any artist changing the lyrics to a song to either make it more germane to themselves or to the times, it falls well under the rules of artistic license for a live performance, and makes total sense in the current climate. If anything, Early James deserves to be applauded. Joan Baez inadvertently changed some of the lyrics to the song in her version, misunderstanding them from the original recording. And no different than a parody, performers have the right to express themselves however they choose, and to use a previously-written song as a template. Some may see Early’s effort as being in poor taste, but it’s not inherently problematic.

The issue is presenting the original lyrics to the song as problematic, which Early James and an article in Rolling Stone entitled “Can The Night That Drove Old Dixie Down Be Redeemed?” does. Writer Simon Vozick-Levinson calls it a “troubling requiem for the Confederate cause” and “a vehicle for a harmful, racist American myth,” but offers no real argument of why this would be the case. This is certainly a different opinion than what Rolling Stone shared about the song on their Greatest Songs of All Time list in 2011, calling it “moving,” and said it “evoked the interior struggle of someone trying to make sense of a lost cause,” and praising it as having a theme that paralleled the Vietnam War well, which was raging when the song was originally released in 1969.

Of course, the earlier opinion from Rolling Stone is the correct one, and the one most universally-recognized. Does anyone really believe that Joan Baez would sing something she though could in any way be considered “a vehicle for a harmful, racist American myth,” or that Levon Helm would sing a “troubling requiem for the Confederate cause,” or that Robbie Robertson would write something that could be characterized as such? But this isn’t just about intent. Of course, everyone can interpret songs differently. But it seems like very few were interpreting the song as racist, and those that are seem to be solely basing those opinions off of surface takes on a nuanced song. They see terms like “Dixie” or names like “Robert E. Lee,” and make assumptions about intent that are not born out in a greater assessment of the lyrics, or the context of the song’s writing, performance, or performers.

Robbie Robertson has told the story of how he wrote the song on many occasions. It was inspired after Robbie went to meet Levon Helm’s parents in Arkansas, who lived in a home on stilts. Later Levon Helm took Robertson to a library in Woodstock, NY so he could research the American Civil War. The story of poor Virgil Caine is told through the campaign of Union general George Stoneman, whose raids behind Confederate lines—and specifically the destruction of the railroad tracks in Danville, Virginia—are given credit for breaking the back of the Confederate army which was starving in the winter of 1865, unable to resupply.

Virgil Caine is the name, and I served on the Danville train

Till Stoneman’s cavalry came and tore up the tracks again

In the winter of ’65, we were hungry, just barely alive

By May the tenth, Richmond had fell, it’s a time I remember, oh so well

Does this sound like glorification? Robbie Robertson specifically addressed any concerns with the song in a SiriusXM interview in late 2019. “I’m sitting down at the piano writing a song, and something creeped out of me, and it was a story,” Robertson explains. “And I was writing a movie. I was writing a movie about a Southern family that lost in The Civil War, and from their side, but the story of that family. I was trying to write a song that Levon could sing better than anybody in the world. And that’s all it was. That’s what it meant to me—-this little movie, a perfect thing for him.”

“The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down” is quite literally the story about the defeat of the Confederacy, in no way glorifying its cause, or slavery, told from the perspective of a poor Southerner from Tennessee who would have not been in a position to own slaves, and due to conscription, would have been forced to fight in the Confederate army, or face imprisonment or execution. It is difficult to impossible to construe the song as racist, but the Rolling Stone article fails to go in depth about the content of the song, or how it was written, and doesn’t even mention the major hit Joan Baez had with it, robbing readers of the critical context with which a case of the song should be presented in.

It’s also understandable why some might find “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down” as problematic or offensive. It does mention “Dixie” in the title. It does reference Robert E. Lee, which some may find polarizing regardless of the context. But it is at least worth presenting the song within a proper context instead of assuming and assigning racist intent to it, and not allowing for any discourse on the matter by leaving out critical counterpoints.

Though diving into comments on social media can be a fool’s proposition, reading through them shows that the vast majority of Rolling Stone‘s own readers strongly disagree with their characterization of the song.

Always saw this song as a lament about the destruction caused by the rebellion and Virgil Cain’s realization that this widespread disillusion killed his brother and destroyed the lives of millions.

Personally I never thought of this song as confederate “anthem” and I don’t think changing the name will have any impact of the modern day civil rights movement. I always thought of this song as a ballad. Nothing more. Its not the Confederate Flag.

Mixed feelings about this. Seems appropriate for our times, yet there’s also something dangerous about bowdlerizing art.The weird part about all of this is that the song is not necessarily hagiographic towards the confederacy. In fact, the verse that got the most change was the one where the speaker mourns his brother’s death. Southerners have no feelings, no contradictions, just mindless bigots?

The lyrics to this song are clearly spelt out as anti war and anti confederacy. These changes destroy any subtlety the original possessed. And for Rolling Stone to boil it down to a confederate anthem is woke baiting.

…and the sole comment in agreement on the Twitter thread:

Wow. They sang with such fervent emotion about their right to keep humans enslaved for capital gain. This really puts the sacrificial slaughter of our children by sending them school for the economy into perspective.

Also troubling was Early James’s proclamation, “I hope we piss off the right people by changing these words,” which he said before singing his edited version backed by the band of Marcus King. By “pissing off” people who may have taken offense to his take on the song, this would not work to break down racism, broaden perspectives, or open people’s minds to the continued challenges African Americans and other minorities face in the United States. Instead, it’s anger and a lack of nuance that sends people into the arms of extremist groups who can then exploit that anger and conscript new members—something that assigning racist intentions to clearly non-racist institutions such as “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down” does on a regular basis. Rebuking the song could just as easily result in more racism than less.

Early James was just looking to express himself in this critical time for race in America, and using the template of “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down” to do so is fine, if not commendable. But for either Early or Rolling Stone to insinuate the song had racist intentions to begin with is not only incorrect, it’s arguably counter-productive to the cause. Not everything that makes reference to the Confederacy is racist. The Civil War was an indelible part of American history that artists in whatever medium should be able to make reference to without fear of retribution as long as it’s not glorifying racism.

Furthermore, now that the slippery slope has slid into assigning racist intentions and messaging to a song that most of all was meant as anti-war, the next question is, what is next? Will The Band, Robbie Robertson, Levon Helm, and Joan Baez be called racist for singing it? Similar to the attack on “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down” which we knew was coming, it’s likely not a matter of “if,” but “when,” while few step up to offer context or nuance, fearing they will be labeled racist themselves.

August 8, 2020 @ 8:45 am

Wait till they hear White Mansions.

August 8, 2020 @ 9:07 am

I shall endeavor to see that Early James has an early retirement from the music business.

August 8, 2020 @ 9:10 am

Yeah, let’s not counter cancel culture with cancel culture.

August 8, 2020 @ 10:20 am

Idiots should be cancelled . . . PERIOD!

August 8, 2020 @ 11:43 am

Big Tex, Early James is not an idiot.

August 8, 2020 @ 12:42 pm

Lefty:

If the quotes attributed to Early James in Trigger’s article are accurate, then Early James is an idiot.

August 10, 2020 @ 7:28 am

we’re gonna miss you around here in that case, big tex.

August 9, 2020 @ 8:17 am

Once again you are so far off base as to be almost funny if it weren’t such a serious subject. It’s time for you to retire. You’re letting your extreme right wing politics cloud your judgement

August 9, 2020 @ 8:22 am

Kenny:

I think I hear your mommy calling you.

August 9, 2020 @ 8:29 am

It’s “extreme right wing politics” to say we shouldn’t try to cancel people who try to cancel people? Seems like a bit of an overreaction.

August 9, 2020 @ 4:32 pm

I love “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down.” In a lot of ways, it reminds me of the late Tommy Crain’s “Lonesome Boy From Dixie.”

January 23, 2021 @ 11:09 pm

I don’t want to cancel anyone. Early James has the right to sing the song with modified lyrics. But the new lyrics are terrible and are an insult to Robbie Robertson, Levon Helm, and everyone else associated with the song. The song consists of one fictitious man’s story from 155 years ago and should be left alone.

Might as well change the words to Shakespeare’s Henry VI, Part I because Joan of Arc wasn’t really a witch.

March 31, 2021 @ 3:02 am

I was drafted into fighting the war in Nam, as a citizen soldier. I understand the disillusioned grief, confusion, and anger as Virgil Kaine sorts through painful memories as I heard heard “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down.” My people called on me to serve, I did so with distinction, three times I was awarded honors, two bronz, and a silver. At last doing the extra one more time I paid for that a act by loosing a leg, and two years in a hospital recovering I did not accept the advice to not be seen in my uniform. If you do you will be vilified and say the lover of war, and a killer of babies. I was the Virgil Kaine of the 1968 Tet Offensive. When Joan Baez sang I wept, and I did not weep alone many grunts, my brothers wept as I did. When a war is not popular the men, and boys who fight that war are shamed as villains. These were different Wars fought for different reasons, that it came down to the same shame.

April 10, 2021 @ 9:23 am

Thank you for sharing your story. I will always of think of this when i listen to this song in the future.

March 19, 2022 @ 9:21 am

I thank you for your service. I know how hollow that can sound. I am a veteran. I never experienced the horror of war. I do understand fighting to protect yourself and your cohorts. There is no shame in what you did!

August 8, 2020 @ 3:16 pm

How’s that?

August 8, 2020 @ 8:14 pm

Jake:

Ask Natalie Maines.

August 8, 2020 @ 10:12 pm

You claim responsibility for that?

August 9, 2020 @ 8:20 am

Jake:

Not solely. There were lots of patriots who assisted me in that mission.

August 9, 2020 @ 8:52 am

Um….let’s see here….are you sure you want to call actively trying to silence someone’s voice as patriotic? To the US? To our ideals such as free speech? I’m all for you expressing your opinion about them, and right to boycott, but why do you feel the need to take it to the level of silencing them? I’m no fan of any of these artists and I disagree with what they’re doing, but if you don’t see the irony here I’m at a loss. Fortunately, I don’t think there’s many on the right that are behind you on this anymore…that authoritarianism seems to be coming mostly from the left these days.

August 9, 2020 @ 9:15 am

Authoritarianism from the left?The right never stops screaming about the constitution & free speech,but if anyone DARE question or disagree with our current dictator they are told to shut up!how does this ideology work in your heads?somehow if it’s their guy in office I’m unpatriotic to disagree with the king?this is how,RAGING HYPOCRISY.the same kind that tells you you’re a Christian,but give the biggest tax break to billionaires,but the working class needs to suck it up.you,much like the president ,are incapable of empathy..quit waiving that bible & constitution and read it.

August 9, 2020 @ 9:31 am

Well, that didn’t take long.

I know some of us wake up every morning wanting to cry orange man bad at every possible juncture, but this article, and my comment are talking about censorship, cancel culture, and revisionist history. You might have some points there, but I’m trying to stay on topic and check my TDS at the door, for just a minute. Your comment is very telling though, and arguably part of the problem.

August 9, 2020 @ 10:52 am

Jake:

I never said ANYTHING about “silencing” him. I never said anything about “censoring” him. I dare you to find those words in my posts. You mentioned that you respect the right to boycott someone. GOOD FOR YOU! It just so happens that if enough PATRIOTS boycott that idiot, as I shall do, then he suffers for his idiocy. There are consequences to being an idiot; and in his case losing a portion of his audience is one of those consequences.

August 9, 2020 @ 11:12 am

“Seeing that he has an early retirement” kind of led me to read your comment that way. Seems like he’d be kind of silent in his retired from making music state. The Dixie Chicks reference also doesn’t lend itself to merely a personal boycott either….

But thanks for clarifying.

August 9, 2020 @ 11:23 am

Jake I agree 100% What part of this is “Liberty?” To suppress other peoples freedom of SPEECH, because their feelings are hurt. … Making people in fear to Express anything, because of offending other peoples feelings, HOW CAN WE GROW: NEVER HEARING THE OPPOSITION? Conformity that leads to your own disaster.

August 9, 2020 @ 4:59 pm

Erickstein:

Everything you stated in your post, with the exception about conservatives revering the Constitution and free speech, is simply not true. Not true at all.

You are Exhibit “A” that I use when teaching people about “Trump Derangement Syndrome.”

March 30, 2022 @ 7:23 am

Nobody takes the time to find out the original intent of things such as songs anymore. We are a reactive society that is losing the ability for critical thinking. Just a few words and this song has to be racist. Sounds like some people are trying to use this song to get some people upset to forward their career or they’re too stupid to understand it’s meaning.

August 8, 2020 @ 9:21 am

One of the few songs from my mum’s record collection I actually liked. Being a kid and not being from the US I used to think this song was about a train.

August 8, 2020 @ 9:42 am

I agree with a lot of this except the piss off the right people” comment. There are people who are way past convincing anything. This is just the reality of any conflict. And sometimes the only way to say what’s true and needs to be said is to piss them off.

August 8, 2020 @ 10:19 am

The problem is who don’t get to choose who you are pissing off. You might piss off the wrong people, especially if your take on a song is seen as nearly universally incorrect, which it is in this instance, and pushes people away from the message you’re trying to serve.

August 8, 2020 @ 12:03 pm

But that, I think, was the point of his comment. He was going to say what he thought needed to be said about it based on his experience. I watched it live and was struck by how nervous he seemed about it. I think he was really worried that it would be seen as sacrilege by people that he respected rather than what he was aiming for. It just didn’t strike me as troll baiting. I think you are wrong about that.

I really don’t agree with your basis either. Lack of nuance is a problem but in my experience it’s not primarily what drives people to reactionary politics. He makes a key point about his experience in this article that I think you elide to make your own point. His understanding of the song came from how people around him growing up understood it. This is the way art most frequently works. Neither this not Sweet Home Alabama were celebrations of the lost cause yet both were adopted by people who saw them that way. The Rolling Stone writer really blew this article IMO because they didn’t explain the more nuanced history of the song in the context of what Early was doing well enough.

The thing about all this flag iconography and reactionary politics is how it’s shifted and reinvented itself. You almost see it more in the rural northeast than the south now a days. This started in the 70’s and 80’s when I was growing up in rural Pa. With the proximity to Gettysburg we were steeped in the Union iconography our great grandfathers put up but it had grown musty and faded. It was only relevant to history buffs. The confederate flag ,however, breathed through rural culture all over America with the Duke Boys, Lynyrd Skynyrd, Nascar, and so many country music album covers. I spent a lot of years trying to explain this to people who didn’t grow up with it and generally got called a lot of names for my trouble.

But the thing was I was able to understand was how other people perceived it because I knew history and had some empathy. And the fact was that were I grew up was extremely racist and that bullheaded attachment to old ways is the key part of the attraction to the flag. That’s where reactionary politics comes from. It’s not what makes it to media presentations but it was an everyday part of my reality growing up. People who got really attached and defended it despite the fact that their ancestors fought and died to stop the people who flew it do so because they don’t want to change their old attitudes. I know a lot of people who buy their arguments who are not really racist but I also don’t know anybody who’s had any success convincing them to change any attitudes. Those who do change do when life forces new experiences on them and they learn to adapt.

March 5, 2022 @ 10:22 am

The singer himself had to distance himself from it eventually. God Damn every last one of you right wing assholes lying in the name of saving face.

August 8, 2020 @ 9:43 am

Trigger, Cody Jinks did an announcement yesterday on his Facebook talking about a shit ton of stuff he’s got coming, including a podcast, a red rocks album, a live album, several albums of country songs he’s been writing during quarantine, and a rock album? Lot to unfold in his post but if you haven’t seen it check it out.

August 8, 2020 @ 10:17 am

Yes, I saw the Cody Jinks post and might post something quickly about it at some point, but will wait for deeper coverage once we have info on these projects, pre-order links, tracks lists, etc. etc. Don’t want to get in the way of whatever buzz cycle he has working.

August 8, 2020 @ 9:55 am

Hmm. I’d maybe guess an “Early James” to be an old Southern Blues singer, but it looks like he’s some Woke ginger from AL. Maybe if he’d dig up the nearest CSA soldier’s grave, salt down the bones and burn them, he’d then feel a sense of relief.

March 5, 2022 @ 10:24 am

Its seems you’re upset that he’s not felating the corpse like you and whoever raised you to be so arrogantly ignorant.

August 8, 2020 @ 9:56 am

The song is a literary tragedy, right? The downfall of Virgil and his family despite or because of his earnest intentions. And maybe in a greater sense, the demise of the old south due to the immoral practice of slavery. I think Robertson’s description of it as a movie is pretty fitting

August 9, 2020 @ 12:11 pm

Hay fellows! You know that the people who were “Dixie, were Americans? The smartest, ingenious people who ever walked the face of the earth.

The wealthiest of the wealthiest of these Dixie people, knew War was imminent, as early as 1859: So they packed up and moved back to Europe. Leaving their so, called endentured servants to survive on their own.

The Second bunch of these wealthiest American Southerners, who wanted to stay invested in the USA… Packed up around 1859 and moved North of the “Mason Dixon Line” and the Ohio River. And they invested in the Civil War!: Because there is nothing like a “Good War for making money!”.

Being that slavery was not profitable in the USA: The majority of this second set of Wealthy Southerners had done stopped using slave labor, as early as 1800, (the shipping companies, too, had found transporting slaves NOT PROTITABLE, by 1800) and they went into having numerous children: Dividing their plantations into small individual farms, with each of their children inheriting his small farm portion, to be farmed by them. (Look at the plantation plat maps after 1807.) Many of these small farms, of the plantation are still owned by their descendants today!

But! When the Second Set of Wealthy Southerners, moved North: Many of their slaves, that remained with them, and they too, moved North with their original owners, as a freed families, that depended on each other for survival: until their deaths. The are buried up North!

This second set of Wealthy Southerners, that moved up NORTH… They are still in business TODAY! YOU SEE THEM AS NORTHERNERS: WHEN IN FACT… THEY ARE DISPLACED SOUTHERNERS…. They played havoc on Abraham Lincoln and his dominating Northern States Representatives.

Now! The third set of Wealthy Southerners: who wanted to remain politically inclined… packed up too by 1859, and they moved to Montreal, Canada and they MANAGED the SOUTHERN STATES IN THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR FROM THERE. They too, freed their slaves in the South, before they left.

Now …ONLY 8% of Americas’ Wealthiest Southerners (who owned slaves) REMAINED IN THE USA DURING THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR! AND FOUGHT IN THE WAR, ITSELF!

Who Abraham Lincoln invaded in the Southern States were the Small, individual dirt farmers: Who had to compete against the Large Planters for FAIR FARM COMMODITY PRICES. For the small Farmers lived had to MOUTH for survival. But the Huge Plantation owners, with slaves, could sale their commodities in bulk, and could take a few pennies less for their commodities; thus, setting the commodity prices.

So I’M SURE THAT THE SMALL DIRT FARMERS WHO FOUGHT FOR THE CONFEDERACY, DID SO, FOR THE WEALTHY PLANTERS “SLAVES!” The South was invaded by the tyrant Abraham Lincoln and his UNION ARMY… THEY FOUGHT FOR THEIR FAMILIES AND THEIR HOMES!!

LINCOLN “SUSPENDED THE CONSTITUTION AND PLACED THE “ENTIRE” USA UNDER HIS “MILITARY RULE!”” Therefore, doing away with “Due Process of Law!” For ALL AMERICANS, NORTH AND SOUTH! There is more to this story!

August 9, 2020 @ 1:30 pm

Whoa …

Laughing.

What a bunch of horseshit

June 5, 2022 @ 2:42 pm

Wow. I’m not sure I’ve heard this much bullsh!t since Donald Trump “acted” as President of the United States of America. You need to check your facts, Savanah. Abraham Lincoln never invaded the south. If that is what you want to believe, no one here will ever change your mind, no matter the facts laid before you.

This song is a beautiful song and it tells a story from a position that not many get to hear. There are zero elements of racism and I hope that we are sensible enough to never force the change of an incredible piece of art literature, and history. Robbie Robertson is a remarkable, brilliant, and sensitive song writer and musician who, even in 1968-69 would never have written and performed something that was indicative of pro-slavery, racism or pro-condeferacy. While he is Canadian, his ethical roots include First Nation and Jewish Heritage, so I’m quite certain he wouldn’t be writing something that implores pro-confederacy. Furthermore, Levon Helm was widely regarded as someone who stood against racism and therefore, wouldn’t sing something that glorified the confederacy.

August 8, 2020 @ 10:06 am

Just another 15 minutes of fame seeker looking for a quick buck.

August 8, 2020 @ 10:10 am

Man, the slippery slope is real. I support taking down confederate statues in public parks, which were erected during the Jim Crow era south. But then they start pulling down Columbus statues, too – sure he’s a monster, but they were erected as part of America’s founding myth and a way for Italian Americans to integrate with American culture, not as a symbol of oppression. Can’t these considerations be weighed? And let’s not even talk about those who want to take down Jefferson or Washington statues. Please. And sure, Trader Joe’s could and probably should change the names of their “Trader Ming’s” and “Trader Jose” brand food, a cute idea but maybe a joke that’s run it’s course. But along with it, the owner is being asked whether the store name “Trader Joe’s” is racist because he said the name was inspired by reading an old book that includes racist characters and ideas. So now he is to be judged by whether he thought racist thoughts at a certain point? Really? And how is the word “Antebellum” inappropriate? It marks a period of time, not what happened in it. Are we no longer allowed to discuss America before the civil war? Are we no longer allowed to tell stories about confederate soldiers at all? Will libraries pull the John Carter Mars books from libraries, because he was a Virginian? Are we to purge all mention? To be clear, I absolutely support a clear eyed reckoning with all the “war between the states”, “states rights” mythic nonsense surrounding the civil war designed to obscure the fact that the war was waged to keep human beings as property. I would be happy to never see a confederate flag wave ever again. That’s important work and must continue. But boy, there is a lot of nonsense going along with it that gives those who are against re-evaluation plenty of ammunition, and that makes me increasingly sympathetic to their position.

August 8, 2020 @ 10:22 am

Columbus was among history’s worst butchers. The evil there is to great to be redeemed.

I see nothing wrong with removing statues that don’t represent a country anymore. People need to update their old ideas.

I can agree with you if we get to the point where we are removing Washington etc. But then I may be to old. The way America can be a democracy that survives is by being willing to update calcified ideas that are not doing us any good anymore. That’s what we started with and every bit of progress we have made involves it. Us old farts just have to get out of the way sometimes. Reactionaries ruin countries.

August 9, 2020 @ 6:00 am

“history’s worst butchers.”

Dude, Columbus has nothing on butchers like Stalin, Pol Pot, and Mao and other Communist heroes.

Hell, guys like Tamerlane, Genghis Khan, and Saladin far outstrip his murder count. Columbus is far down on the list.

August 9, 2020 @ 9:19 am

Despite the world being mostly a warring, brutal place in almost every culture throughout most of history, anything to do with America is now exclusively to blame for the disruption of the utopian paradise we were meant to be living in. Resist!

August 9, 2020 @ 9:34 am

Exactly what the Nazis did, John R. You are a fucking fool.

August 9, 2020 @ 9:54 am

^

August 8, 2020 @ 10:17 am

Over the past year I have heard people complain about a multitude of artists (Charlie Daniels and Lynard Skynard come to mind) Like Rodney Crowell sang “Ignorance is the Enemy” .

Also, don’t the think Confederate backs were broken in 1965…

August 8, 2020 @ 10:17 am

Fuck this guy and the whole woke movement. I’m sick of people altering, changing, erasing shit. This song doesn’t glorify the confederacy. Furthermore, if you are doing a Last Watz tribute show you don’t change the lyrics of an iconic song from an iconic show, it becomes a parody at that point. Also, fuck Macus King for being part of it.

August 8, 2020 @ 10:34 am

Yes, this ^. Learning from history is much better than erasing and/or rewriting history.

The Early asshole is an opportunistic, no-talent ass-clown trying to make a name for himself with shallow “woke” pandering.

August 8, 2020 @ 10:35 am

Artists in the Americana scene—which Early James and Marcus King squarely are—are being put in a very difficult situation at the moment. They are being demanded by peers and journalists that if they don’t engage in aggressive activism, they are direct parties to racism. If they speak out, they’ll get positive press, like Early James did. If they don’t, they will end up on an “accountability list” and will likely receive less press coverage, and less radio play, awards, and touring opportunities. It’s not enough to be a good person, to let the public know you’re against racism with your actions, and act in a way that uplifts all voices. You have to participate in performative actions such as this, or you will be ostracized. It is putting these artists in a very difficult situation. I’m not excusing ANYTHING. But I do believe the music from these artists should be considered on its own merit. This was my very concern with the lyrics of Jason Isbell’s “Be Afraid.” Goading other artists into activism doesn’t always go well.

August 8, 2020 @ 2:33 pm

I’m all for progress, equality, and I’m liberal at heart. This cowardly behavior is beyond creepy. It’s cultish, brainless conformity that reminds me of some dark places that we don’t want to go, if we want to really talk about the slippery slope. At one point, the status quo was the pearl clutching, sanctimonious right wing. Now it’s a bunch of pearl clutching, sanctimonious virtue signalers. Fuck these self righteous, performative, evangelist crybabies.

August 8, 2020 @ 3:44 pm

Just think, in 2006, Charlie Daniels was awarded the “Spirit of America Free Speech Award” by the Americana Music Association.

Today’s “Americana scene” is a far cry worse. I can’t imagine the current lot even considering a conservative, moderate, or anyone who isn’t a far left, “woke” idiot.

August 8, 2020 @ 6:51 pm

14 years ago eh? Can’t wait till 2034, when we celebrate the posthumous stripping of that award, followed by 2 minutes of Charlie hate, accompanied by the pure, sanitized tones of the Ministry of Anti-Americana approved The Highwaythingx. I’d call it a barn burner but barns are problematic to animals.

August 8, 2020 @ 4:16 pm

I don5 necessarily disagree with you but someone needs to make a stand on the face of things getting too ridiculous. This shit is getting too out of hand. Being against racism should be and is enough. I have really never let a musicians politics turn me off their music but this shit does. I don’t agree politically with the majority of the artists that influence me as a songwriter. All this activism is to be trendy etc. I think in the long run it will prove to be a major mistake.

August 8, 2020 @ 1:56 pm

Changing lyrics to fit your feelings and personal beliefs is always allowed for the performer. Johnny Cash changed lyrics to both NIN’s “Hurt” as well as John Prine’s classic “Sam Stone” based on his religious beliefs. He didn’t feel proper saying “Jesus Christ died for nothing, I suppose” so he replaced the entire line. John Prine didn’t mind.

August 8, 2020 @ 4:19 pm

Cash change a couple of lines, he didn’t change a whole fucking verse and its meaning. I can’t believe you are comparing this bag of dicks with Cash.

August 8, 2020 @ 4:51 pm

This guy just changed a couple of lines. When it’s done by someone you like it’s OK, but when it’s done by someone you disagree with it it’s a crime against humanity.

August 9, 2020 @ 7:04 am

I never said it was someone I liked Cash. I really don’t care about him either way. That being said, Cash literally a couple of lines. He didn’t change a whole verse and changing the intent of the verse. When you rewrite the entire verse it becomes a parody. No, it is not a crime against humanity. It is fucking stupid to change the lyrics to pander to a certain demographic. He said we wanted to piss people off. He wanted to get his name out there and used this song to do it. It was a tribute show. You tribute the show as it was. You don’t parody or reinterpret.

August 9, 2020 @ 7:15 am

This change didn’t change the meaning of the song. It slightly altered the tone and changed the meaning of those couple of lines. That’s clearly been allowed for cover songs since the dawn of recorded music.

Zac Brown’s “Dress Blues” changed the line “What did they say when they shipped you away, To fight somebody’s Hollywood war?” to “What did they say when they shipped you away, To give all in some God awful war?” This entirely removed the political bent of the original by Isbell. This was to pander to more general country fans who wouldn’t stand for Isbell’s politics. Should Zac Brown not have been allowed to make that change?

This has been done over and over again in the history of Country Music. You are allowed to reinterpret whatever you want. If a cover of a song is supposed to be exactly like the original without interpretation then there isn’t a point in doing a cover song at all. Just go listen to the original.

August 8, 2020 @ 6:33 pm

But they soon found that secession was a bigger mouthful than they could swallow at one

gobble. They found the people of the South in earnest.

Secession may have been wrong in the abstract, and has been tried and settled by the arbitrament of the sword and bayonet, but I am as firm in

my convictions today of the right of secession as I was in 1861. The South is our country, the North is the country of those who live there. We are an agricultural people; they are a manufacturing people. They are the descendants of the good old Puritan Plymouth Rock stock, and we of the South from the proud and aristocratic stock of Cavaliers. We believe in the doctrine of State rights, they in the doctrine of centralization.

August 8, 2020 @ 6:36 pm

John C. Calhoun, Patrick Henry, and Randolph, of Roanoke, saw the venom under their wings, and warned the North of the consequences, but they laughed at them. We only fought for our State rights, they for Union and power. The South fell battling under the banner of State rights, but yet grand and glorious even in death. Now, reader, please pardon the digression. It is every word that we will say in behalf of the rights of secession in the following pages. The question has been long ago settled and is buried forever, never in this age or generation to be resurrected.

August 9, 2020 @ 3:36 pm

Johnny Cash actually performed The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down on his syndicated TV show! He did not change it!

August 8, 2020 @ 10:19 am

the night they drove old dixie down is not even in the top 20 of the songs from robertson, helm and the band.

August 8, 2020 @ 10:53 am

According to secondhandsongs, it’s The Band’s third most covered song, with 73 other artists covering it.

I backed into The Band via enjoying the last couple of Levon Helms’ albums. When I went back into The Band’s catalog, the most recognizable song was “The Night..”, so I’d argue it’s probably one of their most widely known songs.

You may as well assert that “Dust in the Wind” was no biggie for Kansas.

August 8, 2020 @ 12:12 pm

Clarification: not in my personal top 20.

August 9, 2020 @ 1:29 am

I deeply re-connected with this song just a few weeks ago, in light of present cultural conflicts.

Nostalgia for the South in rebellion has always been difficult for me to comprehend; the Band’s song is a best way I have found, to connect with the _emotional_ power of the “lost cause” in Southern imagination.

Obviously, it doesn’t glorify the rebellion, or romanticize it other than to make the experience of loss and grief palpable.

Reading the lyrics this summer, I noticed what I hadn’t grasped before: “you can never raise a Caine up from defeat” is not only a cute play on words, but is also a really perverse statement.

It’s an insistence that not only are we beaten, but by God we’re going to STAY beaten. Why would anybody proclaim that???

But it’s the exact truth for many white Southerners: endless rehearsals of failure, bitter feelings of victimization, and the careful nurturing of grievance long after all the participants were dead.

It’s Robertson’s genius, to have captured this twisted complex of ideas and emotions in so few words.

I don’t see how anyone could understand this song, and at the same time see it as a promotion of the Confederacy or anything it stood for.

August 8, 2020 @ 10:32 am

This is my favorite song from The Band. When you view the Last Waltz and take in the performance, it is impossible not to feel something deep in one’s soul. Elementary educated, basement dwelling and irrationally thinking liberals can’t even begin to understand the deep meaning of the song.

August 9, 2020 @ 7:02 pm

Really? Cause I’m a college educated non Republican (libtard or whatever y’all wanna call it), and I love the Night They Drove Old Dixie Down, Rebel Soldier, Johnny Boys Bones, Line Pine Hill, and countless other folk songs on the subject. I also don’t give a fuck about the Confederate flag or any statues. If the locals wanna do away with them; so be it… I’m not about banning things, cancel culture, whitewashing, or anything else.

Your painting would be better if you used a not so broad brush. I don’t pretend to know you or lump you into any preconceived notion I have about people that don’t agree with me on certain subjects.

For the record… James’s new lyrics suck.

August 20, 2020 @ 12:11 pm

‘Dixie’ is my favorite song of all time, also! I just wish I had written that one. There is one ancient southern phrase that sums the objections to this perfect song. ‘Chicken Shit!’

December 14, 2023 @ 5:36 am

This was a great article and I learned a lot. Thank you.

August 8, 2020 @ 10:42 am

It was this idea of cancellation that drove me to conceive of an album of Stephen Foster’s music 16 years ago. Foster is, by most accounts, one of the ten most important musicians/songwriters in American history, even though he would use some unfortunate verbiage in his songs, especially by today’s standards. I’m old enough that I grew up singing Foster’s songs in kindergarten in the late 1960s. Then in the early 1970s, Foster was just….gone. Or his music was used as a signifier for racial bigotry in popular culture, as in this scene from Blazing Saddles (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0H2W1lK7P-I). With the dawning of a more enlightened view on race, people just didn’t feel comfortable singing songs with the N-word and “darkie” in the lyrics. And I get that. Who would want to sing those lyrics now? We allowed the artists to sidestep those lyrics, and we got an amazing array of artists to participate – John Prine, Mavis Staples, Raul Malo among others.

The point of that album was to look at Foster through the framework of race. He became very famous from his minstrel songs (essentially the 1840s version of appropriating black culture) like “Camptown Races” and “Oh! Susanna,” and then got consigned to the dustbin of public consciousness because of the discomfort discussed above. One of our most important songwriters’ career was entirely bracketed by race. In my opinion, a fascinating topic, and one that we would be the poorer for if we just summarily dismissed Foster, never to speak of him again.

Foster had a mixed record in his lifetime on race. He was a supporter of President Buchanan, who was neither a supporter of slavery, but was enough of a milquetoast moderate that his inclination was to try to compromise the slavery issue away, thus keeping tensions enflamed on both sides of the issue. And of course there were his lyrics, some of which look unfortunate from our vantage point 170 years after the fact.

He could also show signs of empathy toward the slave community. He wrote a song called “Nelly Was A Lady” that was a sympathetic story of a slave that had lost his wife, and when Foster sent the song to the minstrel troupe that was going to perform it, he told them that if they did not sing it with respect for the protagonist, he would never send them another song. He also wrote a slew of achingly beautiful songs that have nothing to do with race, as well a number of patriotic songs that bolstered Union spirits during the Civil War.

And isn’t that very American? Flourishes of empathy littered with episodes of galling insensitivity and general cluelessness about how to navigate issues around race, gender and sexuality? So what do we do about this cluelessness as it unfurls in real time?

Philosopher George Santayana famously said that “those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” We have seen that play out many times on the world stage, and it’s my opinion that we’re never served by refusing to acknowledge cultural artifacts from certain times, or even interpretations of that history that are produced after the fact (like the song that spurred this article), which are no less part of the historical record than the events that are being interpreted.

I think one of the reasons that Germany has been relatively successful in keeping fascism at bay is that they neither hide from their history, but nor do they glorify Nazi leaders with statues. If they did not welcome a robust internal discussion about their Nazi past, conversations would still happen without a national countervailing narrative that what happened to the Jews in the Holocaust should never, ever happen again. They did not cancel the Nazis, but acknowledged that this happened, that the perpetrators were their parents and grandparents, and their refusal to cancel them is a tool of accountability. I was in Hamburg not long ago (although it seems a lifetime ago now), and they have plaques embedded in the sidewalks outside the houses where Jewish families who were exterminated lived. That it happened within the lifetimes of my parents is a powerful reminder that this heinous past is not that far in the past.

Sorry, kind of went down a rabbit hole there for a second, but my point is that we need to talk about this shit, and not reflexively “cancel” those who don’t completely align with our viewpoints. It’s how we can stick together as a people, as a nation. In canceling those that are making slower progress than we would like on the path to embrace social justice, we push them back into the dark corners, and make them feel as though they are not welcome at the table of brotherhood. It’s in those dark corners where the Dylann Roofs grow into monsters. He was so far gone by the time he arrived at Emanuel AME Church, even when he was welcomed by and prayed with the congregants, he then turned around and massacred them, because the rot had set in so deeply, he could not conceive of their humanity, even when it was being demonstrated before his very eyes in the hour before he killed them.

Talking about all of this in relation to “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down” might seem like bringing an elephant gun to a leg wrestling match, but this seemed as good a place as any to get down my thoughts about cancel culture. Certain things are binary, but not everything is. I have very good friends who are conservative (I am not), and I am better for knowing them as good people, who just have a different view on how much government should be involved in certain aspects of civic life. They are also better for knowing someone who tries to be thoughtful in my critiques about tax rates, how our country deals with medical care, etc., even though they may not share my views.

If we “cancel” one another, the end result, is that we will huddle with our tribes in our own intolerant corners, not allowing or welcoming a dissenting viewpoint, which we might actually learn and grow from, and which robs us of the opportunity to encourage more tolerance. When we demonize our intellectual opponents, we leave no room for us to live in this place together, to learn from one another, to live up to the dream that MLK had for us being able to sit down together at that table of brotherhood.

August 8, 2020 @ 11:08 am

This dude is an idiot and his music is horrible. Maybe if he wants to be completely “woke” he should stop imitating blues music that was created by slaves and black people living under Jim Crow- not change a classic song about a poor southern man during the civil war.

August 8, 2020 @ 11:22 am

It’s like a breath of fresh air to read some reasonable commentary these days. Thank you. Over-reaction one way will just lead to more over-reaction the other way. Too many people are moving to extremes, both right and left. What this country needs right now is balance. We need to move the USA forward together, while we still can.

Personally, I have always liked the song. I don’t think it’s racist in intent or meaning. It’s an anti-war song.

August 8, 2020 @ 11:33 am

The song tells a story from the perspective of the character in the song. Nothing more nothing less. Apparently some people have become unwilling to enjoy art of all types as art. Take from the art what you will and leave it be for others to enjoy in their own way. It is a damn shame our society is in a place so intellectually dishonest as to assume a negative without any analysis at all beyond the emotions of this time in our society.

August 8, 2020 @ 11:49 am

Been on a huge Dwight Yoakam kick lately. I wasn’t super familiar with his music on an album level before, just the hits.

I’m surprised by how often he references Dixie or Dixieland fondly in his songs, what with his having built his music career in 80’s LA, among the lefty punk rockers, and continues to be one of the country artists liberal non-country music fans give a pass to.

August 9, 2020 @ 7:24 am

Context is key with that statement. Dwight came up at a time where we didn’t have social media thought bubbles on the left and right where people just get to work themselves up in a lather about stupid social issues (while our Country burns economically and socially from a pandemic mishandled by all levels of Government).

Social media is a pox on this Country.

August 9, 2020 @ 5:06 pm

I think Dwight was cool enough to hang out with the most “In” crowd, and in LA if you know the right people it’ll probably insulate you from a lot of close scrutiny. Look how long they turned a blind eye to Harvey Weinstein, and lots of them had to know he was a douche. Now, if Yoakam could be identified with John Wayne on politics, I’m sure they’d be tallying up all of his Dixie references.

August 8, 2020 @ 12:21 pm

People don’t really listen to music anymore. They read something online or see a title and “imagine” they know what it means. This song is an American Music Classic. A character study of post civil war life that glorifies none of it. This is coming from a NY left of center 58 year old guy. Dixie in a song title does not, in and of itself, make the song or the artist racist.

Now those statues of traitors…that’s a whole other story.

August 8, 2020 @ 3:16 pm

Early James strikes me as the kind of guy who would be sure to wear his seatbelt as he drove his wife over to her boyfriend’s house at 9:00 PM on a Tuesday, and then wait patiently in the driveway until she was done, and then after 4 hours of sleep would serve her breakfast in bed before heading off to work to provide for almost all her needs.

As for the song, I’ve always liked it. I don’t feel it glorifies the Democrat Party.

August 8, 2020 @ 3:25 pm

Once heard Natalie Merchant sing live at the Lilith Fair fest. Don’t get much more liberal than that. Yet no one had a problem with it. People are stupid. They’ll be gunning for The Green Mile, Forest Gump and Driving Miss Daisy next. People suck man.

August 8, 2020 @ 6:44 pm

How about people just stop reducing everything to a single category?

August 8, 2020 @ 7:36 pm

The song is clearly a southern gothic fictional tragedy. That said, in my opinion “cancel culture” is so low on the list of actual problems facing our country that it wouldn’t register on the Richter scale of problematical social movements. In most cases someone just wants to be a rude asshole with no consequences or is just unintentionally being ignorant. Of course some innocent people get slammed by the masses unjustly, but to me the problem is mob justice in general. It is a great song though, and it doesn’t seem like the kind of thing your run of the mill klansman would be blasting to get pumped for a cross burning though.

August 8, 2020 @ 8:14 pm

Early James sadly lacks the intellectual capacity to see people and understand them through the lens of history and societal culture of the times. I used to assume most had this ability., but apparently few in the current generation seem to have any ability to think independently, use critical thinking skills , display reason, or utilize outside the box thinking,. At the same time Orwells chilling vision becomes all the more reality.

There isnt a thing wrong with this song. It needs no change, it’s a masterpiece of songwriting. It needs no defense. Contrary to James assessment, its not defending slavery or the confederacy, and yes it humanizes the characters which is important. But, was Early James alive then? Would he really have had moral superiority if he had lived then? Would any of us? You simply can’t answer that question honestly if you weren’t there. Unless you were born at that time and raised in that culture you don’t know. Peoples opinions and actions are shaped by their environment , culture and upbringing. Sure their were abolitionists and anti slavery movements, and there were folks who questioned things, but the vast majority of people weren’t looking to be part of that, they were more concerned about survival, like the characters in the song. And they were human beings too.

Its easy to take the moral high ground when looking backward at a time you didnt live in.

August 8, 2020 @ 8:43 pm

I play quite a few American Civil War tunes (from both sides). Although “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down” is not really a Civil War, I will now have to add it to my repertoire, if only because it will “piss off” the wokesters! But it is a good tune. It’s sort of like the tune “Ashokan Farewell” that is also not an ACW tune, but is now associated with the ACW due to Ken Burns using it in his series on the ACW.

And I was thinking of modifying the words to “Marching Through Georgia” to “Marching Through Portland”….

“Bring the good old cannon boys, we’ll load another round,

Load it with some grapeshot that will strike antifa down!

Let’s clear the streets of rioters, see how fast they ran,

While we were marching through Portland!”

Well, the lyrics need some work, but it would be good to come up with some “modern” lyrics for that old tune. And then maybe the folks in the south won’t have to hate that tune any more.

August 8, 2020 @ 9:14 pm

The slippery slope went from “The confederate flag is racist because it was adopted by the KKK and neo-Nazis” to “Anything related to the south is racist.”

The Dixie Chicks changing their name to “The Chicks” and Lady Antebellum changing their name to “Lady A” is entirely ridiculous. Nothing but virtue signaling going on. No one is trying to bring back slavery and segregation

August 9, 2020 @ 7:37 am

The only segregation that takes place in modern America is between the rich and the poor. The right and the left ignore this topic because the truth hurts, but the reality is the wealthy could give a crap if a black family moves into the neighborhood if that black person is a doctor, lawyer, etc. I guarantee you Charlies Koch or Jeff Bezos don’t care if a neighbor his Hispanic or Asian, as long as that person has the wealth to live in their zip code.

From Mississippi to Minnesota, this is just a fact of modern American life.

April 11, 2022 @ 3:24 pm

But would you deny a fellow citizen their right to do something ridiculous?

August 9, 2020 @ 12:59 am

I didn’t like how the writer of the RS piece takes it for granted that the song is ‘ultimately a vehicle for a harmful, racist American myth’, since it casts all kinds of insinuations at those who don’t believe that. James’ changes, therefore, are by and large going to ‘piss off’ people who think he’s willfully misreading the song, which he is – it doesn’t help that each change is a hammy, rhythmically garbed mess either (how the hell is he fitting ‘I think it’s time we laid hate in its grave’ into the song? The extra syllable sticks out like a sore thumb).

August 9, 2020 @ 1:40 am

Probably the greatest song ever written. I have always marveled at the way the song feels like a movie. How is a story about a man whose life was shattered by the war, racist? Because writers don’t research or even try to get below the surface. Because they don’t have to! Shallow, pathetic Rolling Stone article. Why change the lyrics? Oh, you are too stupid to understand the song….. you think Virgil was proud to be fighting in that war? His life was destroyed. He does not seem too proud of losing loved ones for a lost cause war. This is no proud Confederacy anthem. Did the author even listen to the song? Wow, I am just blown away by no one having accountability for writing garbage like this.

August 9, 2020 @ 1:53 am

I’m as proudly and defiantly liberal as they come, but there’s no way “The Night They Drove Ol’ Dixie Down” glorifies the traitorous Confederacy or needs to be “redeemed.” The song is a personal lament about the high cost of war. Robertson’s method of storytelling here is to take a big issue (the Civil War) and tell it through the eyes of one person. His protagonist could just as well have been living in a Union state — the personal cost was high there, too — but telling such stories from the losing side is generally more dramatic.

Early James can rewrite/add all the lyrics he wants, but at the end of the day, his verse adds nothing to the song, and tries to turn the song into something it is not.

Moreover, if you’re going to add a new verse to a classic song, at least try to keep the original’s voice. One of the things that makes Robertson’s song so gripping is the simplicity of its linear storytelling. There are few thoughts and they are simply told. You can imagine a Southerner from 1865 saying them. There aren’t any inconsistencies the listener has to pause to reconcile.

James’ verse is a labyrinth of abstract thought — 12 different concepts by my count. That is a lot of thinking to ask of a listener. He’s creating a narrative this song’s protagonist would never say and when he does that, the song loses its authenticity and, ultimately, its impact.

August 9, 2020 @ 4:35 am

Just don’t go over to Rolling Stone’s sight please. This is exactly what they are wanting to bait you into their failing publication. You’ll increase their site traffic and drive their hit count and embolden them to encourage more crap like this stunt. That’s all it is. A stunt driven for attention by the singer and the publication. I’m pretty liberal too but I don’t have to be a rocket scientist to know the deal and what is going on. Don’t feed the trolls out there who monetize the politics of today and fan more flames on either side such as what the singer and magazine are doing. Anger makes them money. The “press” of today fuels anger in society to make money for themselves. Got to cut that off from them and not give them what they want.

August 9, 2020 @ 7:30 am

Agreed. Rolling Stone Country for a brief moment in time was a decent site to discover new artists and to see artists featured on this site get coverage on a “legacy media” site. Since Trump was elected, the site has become awful. The only stories they look to cover are clickbait ones that may get some traction on Twitter or Facebook. The Music recommendations have become awful (who gives a shit about Orville Peck?) and they no longer do interviews.

I say all of that as someone who can’t stand our current President. Rolling Stone & Rolling Stone Country needs to die. Bluntly, this is the last music website I read anymore. If this site ever goes away, I don’t know what I will do for discovering new artists/bands and reading thoughtful reviews on artists I currently love.

August 9, 2020 @ 5:58 am

American popular culture is screwed up.

A show about a homosexual Jesus is fine. Serial killers as heroes are fine. American Horror Story is OK. Dozens of degrading and perverted shows and songs are considered acceptable but a lament about a broken Southern farmer is somehow evil.

But some groups are acceptable targets. The South will always be one. And no amount of bowing to the woke group will change that.

August 9, 2020 @ 6:16 am

I’m genuinely curious why the Democrat Party itself hasn’t been cancelled. If we’re canceling anything that was ever associated with racism, they should’ve gotten the axe way before all their statues did.

The Democrat Party was more to blame for slavery than the region known as The South, evident in the fact that there are counties in The South that have voted Republican since before the war.

So yeah, cancel the Democrat Party, and then I’ll believe you’re really trying to fix racism; otherwise I just think you’re a shallow signaler pushing a political ploy.

August 9, 2020 @ 4:23 pm

Honky,

You know why. Same reason why Robert Byrd and Joe Biden were allowed to stay despite racist actions and comments. The (D) is a get out of jail free card.

Their “standards” apply to everyone but them.

August 9, 2020 @ 4:40 pm

Okay, let’s please keep this discussion on topic, and not veer so far into politics. It’s a contentious enough topic as it is. Thanks!

August 10, 2020 @ 6:48 am

Trigger,

I appreciate the sentiment and normally I would agree but this entire process has been political. One party, in particular, has made cancel culture a political weapon. The topic is political. Unfortunately.

August 10, 2020 @ 9:11 am

I understand. But when you bring up names like Robert Byrd and Joe Biden, that can bring up a tangent on those names that have nothing to do with the topic at hand. I agree there’s a political element to this topic, but let’s keep it on this song, The Civil War, etc.

August 10, 2020 @ 7:19 am

the democratic party is responsible for slavery? more so than the people that had the slaves and fought to keep them? counties voting for republicans is proof of this?

this might be the stupidest comment in this thread and big tex is participating an awful lot.

August 10, 2020 @ 1:01 pm

This isn’t directed at just gentile, but everyone on this thread. I can answer, with 100% accuracy, who is “responsible for slavery.” Whereas in 2019 there were still an estimated 40 million people in slavery around the world, whereas it has existed on most continents, throughout most of history……….it isn’t Republicans or Democrats who are “responsible for slavery”….it’s…..wait for it……it’s human beings. Not white, not black, not brown, not any other subdivision. It’s all of us. Pretty much everyone alive has ancestors who were involved with this. We suck. You’re welcome. Now, how many of us are doing anything to help, or even talking or thinking about the 40 million people still in bonds, 25% of which are children, while we argue if it was the Democrats or Republicans…for nothing more than political capital? 🦗🦗🦗🦗🦗

August 10, 2020 @ 1:55 pm

Warlord Joseph Kony, anyone?

August 10, 2020 @ 2:07 pm

I heard Mr. Warlord is a republican…no wait, I think it’s democrat.

Most of these comments aren’t meant to solve anything. Just like this Early loser changing the lyrics…it’s done to “piss people off.”

August 10, 2020 @ 1:28 pm

It’s hard to know where to begin with someone like you, or even whether it’s worth beginning at all.

So I’ll rephrase it in a way that maybe you’re able to comprehend.

The Democrat Party was 100% pro-slavery.

The South was not 100% Democrat, thus not 100% pro-slavery.

Therefore, the party itself had more to with slavery than the region. The Dems were the party of slavery, but most southerners didn’t have slaves.

Virgil Caine was probably too poor to have slaves. He was a victim of circumstance.

Trigger,

To me, this ties into why the song shouldn’t offend anybody.

August 10, 2020 @ 1:57 pm

Exactly.

But Honky, you have to remember.

People aren’t interested in factual history.

August 10, 2020 @ 2:07 pm

if you don’t know that the democratic party of the civil war is nothing like the party today, i don’t know what to tell you, bub. same goes for the republic party. if anything, they’ve swapped ideologies.

August 10, 2020 @ 2:40 pm

thegentile,

That is a cop-out answer. According to the ideology pushed by cancel culture, once tarnished, forever shamed.

So by their logic, the Democratic Party should be cancelled and discontinued immediately because it supported slavery and blocked attempts at integration. The supposed party switch is immaterial.

Except, the Democrats are given a free pass. Along with Yale and other places. I wonder why….

Cancel culture only wants to cancel those it disagrees with it. If their own side has a sin, well, excuses and rationalizations will be made.

August 10, 2020 @ 2:44 pm

Honky,

Exactly.

Virgil Caine was too poor to even get by. He lost everything because of situations beyond his control. He lost his job, his brother, and his dignity. His story is one of how war is hell.

But for some people, they see the words CIVIL WAR, DIXIE, THE SOUTH, and critical thinking goes AWOL.

August 9, 2020 @ 7:20 am

Every time you comment on a social or political store you make the same broad, sweeping generalizations you, yourself rail against. Serious question, do you consume any news/media that isn’t a part of your Facebook algorithm bubble?

My God, as a Libertarian myself, I am always amazed that people like yourself get so worked up about the “immorality” of Pop Culture, to the point where you want shows canceled, while at the same time being upset that the Left wants songs that glorify the Confederacy canceled. Do you not see the hypocrisy?

August 9, 2020 @ 7:32 am

I too am a libertarian- and I find Triggers accounts as fair and balanced as there ever has been in my time- (I’m 72 and have been paying attention for a LONG time)- a libertarian, IMNSHO, would choose the side of Liberty. Period.

August 9, 2020 @ 7:41 am

My comment wasn’t about Trigger or this site. It was directed at CountryKnight.

I just find this “cancel culture” crap exhausting on BOTH sides. It was wrong when those dumb “Conservative Mom” groups wanted South Park canceled and it is dumb today that idiots want The Band canceled. Let people decide if they want something to go away with their dollars and attention. I don’t want CountryKnight dictating if I get to watch a show about Gay Jesus anymore than CountryKnight wants the “left” dictating what songs he can listen to.

August 9, 2020 @ 9:48 am

King honky,I think you would be more comfortable on 4 Chan,with like minded individuals…

August 9, 2020 @ 10:41 am

If you’re going to get triggered every time someone criticizes the left or Democrats, you might not make it the same 5+ years that the dude has been commenting here. Thanks for trying to protect us all from diversity of thought though, you’re my hero.

August 10, 2020 @ 6:37 am

Jake,Thank you for trying to protect us all from diversity you are my hero as well

August 10, 2020 @ 10:13 am

Huh. That’s odd…cuz i’m all for diversity AND diversity of thought. But for you, it’s one or the other? Sounds kinda binary. Do you also trip when you’re trying to chew gum?

August 9, 2020 @ 4:21 pm

Please point out where I asked for those shows to be cancelled.

Yeah, I thought so. Because I didn’t say to cancel them. Learn reading comprehension.

All I said was that some topics are perfectly fine while other topics aren’t. So I find it silly how hypocritical and transparent popular culture is. It is OK to make the Founding Fathers black but ScarJo can’t play a transgender character. For the former, it is considered acting. For the latter, it is wrong! Why the double standards?

Those shows can exist. I don’t watch them. Never will. I am allowed to comment how shows can like that denigrate the religious figure of the majority but a song that might offend a minority must go because it fits agendas.

So you missed the boat on hypocrisy. Try again to score those woke points.

August 9, 2020 @ 4:56 pm

Who knew it would be this hard for some people to understand the difference between stating an opinion and actively attempting to cancel someone.

The double standards you hit on are becoming so rampant and blatantly obvious that it almost seems too pedestrian having to point them out. Yet here we are, stuck in an episode of the Twilight Zone.

August 10, 2020 @ 6:55 am

Because those people are trying to be “fair” and judge both sides by the same level. But life doesn’t work that way. What is fair is evaluating everything by its own merit and standards.

As you said, pointing out hypocrisy doesn’t equal cancel those shows. Pointing out how some groups and traditions are acceptable targets while other groups are sacred cows is just observation.

Popular culture can create whatever it wants. Just don’t expect me to stay silent while the same people that praise anything goes mentality are clutching pearls over a song about a broken farmer. The trash on some shows is a thousand times more damaging than this song. All this song is doing is recording the lamentation of a poverty-stricken farmer who lost everything. But it is the source of outrage while some Gay Jesus is considered bold. Frankly, that is screwed up.

August 9, 2020 @ 6:59 am

For me ,as a musician, a piano player (play by ear,all my life) the melody of this song has always stuck in my head, it’s one of those build up type songs and I recorded a piano/strings cover of it! IMHO people can read into music,politics whatever they want, but I can’t help but say this is one heck of a great song! If ya want check it out here Listen to The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down ( Cover) by JimFitz…. (Music With Meaning) #np on #SoundCloud

https://soundcloud.com/jimfitz-1/the-night-they-drove-old-dixie-down

August 9, 2020 @ 7:29 am

Trigger, Kyle, whatever moniker you prefer, you once again, IMNSHO, show yourself to be one of, if not the most, fair and balanced “journalist” I read.

Good job- and commenters the same goes for y’all, this time.

I wonder hoe long it’ll be before this https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1yuc4BI5NWU will be “cancelled”- my guess is, not too long.

August 9, 2020 @ 9:58 am

Simon Vozick-Levinson deserves to be sued by any surviving members of The Band and/or their families. He should be fired by Rolling Stone. Talk about stupid–the guy has lost all credibility. There is absolutely no way to listen to the song or read the lyrics and come away with anything offensive, racist, or bigoted. Fuck off, dude. What a loser. If Rolling Stone has a moral compass, he should be immediately fired and blacklisted from ever working in journalism again. You can voice your opinion. You can take a stand. You cannot, however, lie. He lied, and deserves to be severely punished for it.

August 9, 2020 @ 11:19 am

It seems to me there should be grounds for a copyright lawsuit. It would be like painting Mona Lisa’s face black.

August 9, 2020 @ 12:31 pm

Just wondering what would be wrong with Mona Lisa being black. Can you please fill me in?

Actually, the fact that she’s not black is problematic, and indicative of Da Vinci’s hatred of people of color.

August 9, 2020 @ 12:47 pm

Trigger,

If you’re going to edit most of the humor out of my comment, please just go ahead and delete it. Could you not tell that I was using extreme sarcasm to make a point?

August 9, 2020 @ 12:33 pm

Another Woke Social Justice Warrior.. Yawn.

August 9, 2020 @ 1:50 pm

I like that song it brings back memories of the nam also billy McGuire eve of destruction its ironic how old songs tell story’s of how things are today.

August 9, 2020 @ 7:24 pm

The song needs no redemption, totally agree.

And I think some of the demonstrations we’ve been seeing where people say their lives matter while torching cars and attacking bystanders, that stuff is wearing pretty thin and ringing hollow.

I’d like to see an end to this “woke/cancel culture” nonsense and a return to free speech and accountability.

August 9, 2020 @ 8:58 pm

I always saw this songs as a sort of “Look what the war has done to me.”

It start with Virgil losing his job due to the war. He lives through a starving winter only to have his city fall from the confederacy.

Next the confederacy takes everything they need, the very best of everything (supplies and probably soldiers).

Lastly he reflects. His father work the land and his brother has gone, then you realise, he’s not even fighting the war. He is a man trying to survive one.

It’s a beautiful piece that Robbie (A canadian) wrote with only help from an Arkansas native. I don’t believe it could ever be seen as glorifying, it’s a tragedy. A man suffering at the hands of a lost cause.

August 10, 2020 @ 5:57 am

I agree. And Robbie Robertson was not just a Canadian, but one of Indian descent. His mom grew up on an Indian reservation in Ontario and Robbie spent a lot of time there visiting relatives, particularly in the summer.

August 10, 2020 @ 1:56 am

I completely agree. The way to address the past is not by ignoring it or trying to whitewash it but by grappling with it directly and honestly. This song was clearly about the impact of the war on the poor in the South and not about glorifying the Confederacy.

August 10, 2020 @ 5:55 am

Who gives a shit there’s nothing wrong with the confederate flag or the song. The civil war was fought over states rights. A major reason for the war was was that the south was getting at least how they perceived as unfair deals involving cash crops such as cotton. The south believed states should have more rights while the north believed that the federal government should. This is a trend that started in the civil war and continues today. Another thing is Abe Lincoln did not want to free the slaves, he did as a way to weaken the south economically.

August 10, 2020 @ 7:27 am

and what was the number one state right they were concerned with? slavery.

the confederacy lasted five years. they lost a war. the confederate flag is a participation ribbon. you might as well fly a white flag. obama was president longer than the confederacy existed. don’t get too triggered by this fact.

August 10, 2020 @ 9:17 pm

I was making the argument that the civil war was about a bunch of conflicts.Slavery was one but not the only one. Lincoln was against the expansion of slavery but not against the states that already had it. In fact states that were not part of the south in the civil war had slaves 6 months afterwards (Maryland). The confederate flag had become a symbol of southern pride and the attitude that you can’t tell me what to do. Only recently it has become problematic. We fly the American flag, and does the kkk so the confederate flag is good because…? To some the American flag stands for imprisonment and destruction of their ideals and traditions. If we take one down we must take them all down.

August 10, 2020 @ 7:34 am

It’s an incredible song and I’ve always loved it. I don’t think it’s glorifying the Confederacy per se, but I think a fair criticism of the song would be that it perhaps traffics in some of that lost cause romance that animated a lot of actually racist efforts. And maybe that isn’t Robertson’s fault, since you couldn’t evoke the Civil War at the time without evoking some of that. It is a romantic song, even if it’s about defeat, otherwise I don’t think it would be so enduring.

I don’t blame an artist for not wanting to sing it right now. It seems like Early kind of split the difference and it really didn’t work out that well for him.

August 10, 2020 @ 7:52 am

This article reduces the issue to whether the lyrics to the song are a problem or not. This is the reason no one can find common ground (or common sense) – we’re constantly being set up to “take sides” as if there is something to be won other than more division and hate.

There is nothing intrinsically wrong with the lyrics, especially when interpreted as I believe they were to be a vignette into the headspace of poor southerners at the end of the war. This is the equivalent to a well-done plaque at a museum giving the visitor insight into the minds of the people involved.

There IS something wrong with it being used IN MODERN TIMES to lament the downfall of the confederacy. When you move from a “documentation of a historical perspective” to a statement of your current, personal sadness about the result of the war, you are slipping into problematic territory, not because of the lyrics, but because of the way you are using them.

Similarly, whatever someone else wants to do to the lyrics is fair game. I don’t like the rewritten version because it doesn’t make sense – it doesn’t jive with the rest of the narrator’s perspective. But I believe the change was made in reaction to the current misappropriation of the song to glorify the confederacy.

There is no right or wrong lyric. Only right or wrong reactions/uses of it.

August 10, 2020 @ 9:09 am

The reason this article focuses on the lyrics is because it’s a rebuttal to another article. I didn’t instigate this discussion, I’m just offering my perspective.

I agree that some could take this song as a lament at the defeat of the Confederacy, and basically use it for racist purposes, which I’m sure happens. But you can’t imprint that interpretation on Robbie Robertson, Levon Helm, Joan Baez, or any of the other performers of the song. Rolling Stone offered no distinction, discussion, or context. The song was racist. And that presents a slippery slope where we’re now calling The Band racist, and Joan Baez racist, which is ludicrous.

August 10, 2020 @ 8:05 am

I have mixed feelings. It’s a beautiful song and the performance in the “Last Waltz” is transcendent. It can be a powerful cover. (In the mid-2000s, I saw The Long Winters join forces with The Decemberists to bring down the house with it at the Crocodile in Seattle[!]).