The Rise and Fall of the Conway Twitty Empire

Listen to this story on the Country History X podcast, available on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, and all other major podcast networks.

– – – – – – – – –

Conway Twitty was one of the most successful country music artists in history. With forty #1 songs on the Billboard Hot Country Songs chart, only George Strait secured more #1’s over his career. Nicknamed the “High Priest of Country Music” by country comedian Jerry Clower, Conway Twitty left a crater of an impact in country music not just with his own songs and albums, but also through his legendary duets with Loretta Lynn, which included 10 total albums, five #1 singles, and twelve total Top 10 hits all on their own.

During his era, Conway Twitty was like country music’s version of Elvis Presley, and not just from his genre-leading success. Twitty actually started in rockabilly and rock ‘n roll, wrote songs for Elvis, and had a similar look to The King with his pompadour and mutton chops. Though this made Conway’s music cool and accessible to a large audience, this always kept him at arm’s length from some country purists. And despite his incredible success, Conway’s only CMA Awards came through his collaborations with Loretta Lynn.

Twitty was also a gifted songwriter, penning eleven of his #1 hits. Scores of other performers recorded Conway Twitty songs as well. Conway’s contributions to country music were massive, but you don’t always hear his name considered when people rattle off their Mount Rushmore of artists in the genre. There are probably a number of reasons for that.

One reason is that Conway Twitty passed away at the relatively young age of 59, denying him that Golden Era victory lap that helps secure the legacies of some artists. Another reason is that some of Conway’s biggest songs may seem a little risque to the modern ear. Songs like “I Can Tell You’ve Never Been This Far Before” and “I’ve Already Loved You In My Mind” probably couldn’t be recorded and released today, though it was Conway’s sex appeal that was also part of his popularity.

For years, large portions of Conway’s catalog were out-of-print. This made it even more difficult for country fans to remain connected to Conway, and for new listeners to take those deep dives into his music.

But perhaps the biggest reason that Conway Twitty’s legacy has somewhat disappeared is that he wasn’t the sharpest of businessmen. Despite being as big as Elvis for a spell and building his own version of Graceland called Twitty City in Hendersonville, Tennessee, it all eventually came crashing down due to an estate dispute in the wake of his passing that split up his assets.

This is the story of the rise and fall of the Conway Twitty empire.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – –

Harold Lloyd Jenkins, who came to be known as Conway Twitty, was born on September 1st, 1933 in Friars Point, Mississippi right on the Mississippi River. He was named after the silent movie actor Harold Lloyd. Music and religion were big players in the Jenkins household. By the time he was twelve the family was living in Helena, Arkansas, and Twitty was already performing in a group called the Phillips County Ramblers. By his teenage years, he was preaching in church revivals. Impassioned and charismatic, Harold Jenkins showed a knack for holding a crowd in his hands no matter what he did.

Jenkins also showed promise as a baseball player and was recruited by the Philadelphia Phillies out of high school. But all of these passions were put on hold when he was drafted into the U.S. Army and served in the Far East. Harold played music when he could while in the armed services, including in a group called The Cimmarons. When he was discharged, the Phillies once again extended their offer to him to play baseball, but by that time Harold Lloyd Jenkins had caught Elvis Presley fever, and he headed to Memphis to become a rock n’ roll star.

In the mid ’50s when you wanted to be in rock n’ roll, Sun Studios and Sam Phillips is where you pointed your nose. That’s where Jenkins landed, but Phillips was focusing on performers singing rhythm and blues, which put Phillips at odds with Conway Twitty’s country and bluegrass influences. Jenkins did record for Sun, but no singles were ever released, except for the song “Rockhouse” that Jenkins wrote and Roy Orbison recorded.

Harold Jenkins did perform with Elvis and others on the Memphis club circuit at the time. In 1957, he officially adopted the name Conway Twitty at the suggestion of his manager Don Seat, who though he needed a name with more star power. The name is a combination of Conway, Arkansas, and Twitty, Texas—two names chosen off a map. For a moment, Conway thought he would record rock material under the new stage name, and his country material under Harold Jenkins, but ultimately decided to go with Conway all the way.

Conway Twitty did okay as a rock n’ roll performer, most notably landing the #1 hit song “It’s Only Make Believe” in 1958. Even though it was a rock n’ roll song, it was recorded in Nashville with country session players such as Grady Martin and Floyd Cramer, and Conway would later record the track as a country song as well. Though it was Conway’s big breakout, some attribute the song’s success to it sounding so similar to Elvis, audiences mistook it as a song from The King.

Conway also hit the Top 10 with the song “Danny Boy” and another called “Lonely Blue Boy” that Elvis recorded for the film King Creole. But with Conway’s religious background and his past dalliances with the priesthood, he became turned off with the behavior and attitudes of rock n’ roll fans. Perhaps this is a bit ironic considering some of the song he would record later as a country star. But during the middle of a 1965 performance in New Jersey, Conway Twitty walked out on the crowd and decided then and there to become a country performer. He moved to Oklahoma City instead of Nashville to set up his home base.

Conway Twitty signed with Decca Records in 1966 and started releasing country albums. Since many in Nashville knew Conway as a rock n’ roll and rockabilly guy, the reception was a little frosty at first. But once Conway landed a #1 song with “Next In Line” in 1968, the ice broke, and Twitty would assemble one of the greatest strings of hits in the history of country music. The songs “I Love You More Today” and “To See My Angel Cry” were other early hits. Then came Conway’s signature song “Hello Darlin'” in 1970, written by Conway himself. It was all over. Conway Twitty was a country music superstar.

Similar to his idol Elvis, Conway called upon sex appeal to create interest in his music. But since this was country, Twitty had to obfuscate the messages a bit more. It was these songs leveraging innuendo that undergirded his appeal. In 1973 when he released “You’ve Never Been This Far Before,” some disc jockeys refused to play it, considering it too suggestive. Though as is often the case, the controversy only fed interest in the song, and it still shot to #1, and for three straight weeks.

This sort of quiet bad boy persona that became Conway’s signature also worked so well though his collaborations with Loretta Lynn who personified the strong country woman who didn’t take any gruff from misbehaving men. Conway and Loretta set the standard for the country music duet, only rivaled by George Jones and Tammy Wynette. Conway and Loretta won the CMA Vocal Duo of the Year award every year between 1972 and 1975.

Along with the incredible amount of #1 songs Conway Twitty amassed, his longevity as a commercially viable country star is just as remarkable. When he landed the #2 song “Crazy in Love” in 1990, it marked Conway’s fourth decade of landing a #1 or #2 hit in country. In fact to go along with all of his #1’s, Conway also had 17 songs peak at #2 or #3. Conway Twitty defined popular country music for nearly 30 years.

By the early 1980’s, Conway Twitty had amassed a huge amount of wealth, and all the success he could imagine in show business. It was then that he set of to secure his legacy and set up his children from two separate marriages into perpetuity. Once again taking a page from the playbook of his hero Elvis, he decided to erect not just a stately home, but a tourist destination where fans could learn about his legacy even after he was gone. It was called Twitty City.

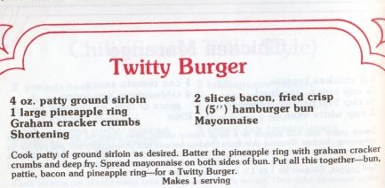

Before Twitty City came about, Conway Twitty had already tried to secure his name and legacy in ways that stretched beyond music. In 1968 after he’d already logged a couple of #1 songs in country and rock n’ roll, Conway thought he would share another signature passion he had with the public, his legendary Twitty burger.

The Twitty Burger wasn’t just your average hamburger. It included a hamburger patty, two slices of bacon, an bun of course, and mayonnaise as the dressing. But what made the Twitty Burger special was the graham cracker-encrusted pineapple set right on top that made the Twitty Burger a delicacy in the fast food space. Not even Elvis Presley’s peanut butter and banana sandwich could hold a candle to it.

Conway Twitty believed so much in the Twitty Burger, he decided to open restaurants to serve it, and envisioned it from the start as a franchise, with locations all across the United States. Twitty even attracted some high profile investors from the world of country music to back his vision financially, including Merle Haggard, Sonny James, and songwriter Harlan Howard. Conway raised roughly $1 million from his famous country music friends and others as investment capital for the franchise.

But Twitty Burger was doomed from the beginning. Due to poor management, Twitty Burger was not around for very long, and was closed completely by May of 1971. “What I know about is how to make records and how to sing songs, and I’m not too good at anything else, and Twitty Burger is a prime example,” Twitty said.

But the legacy of Twitty Burger is still around today due to a landmark case Conway Twitty fought with the IRS, and won. The “beef” the IRS had with Conway Twitty and Twitty Burger had to do with the famous country singer writing off repayments to his investors on his 1973 and 1974 income taxes. In 1973, Twitty took a $93,000 business expense on his taxes, and in 1974, and additional $3,600. The problem the IRS found was these business expenses had to do with Twitty Burger, but were declared under Conway Twitty’s country music earnings.

When Twitty Burger went asunder, Conway decided that the only honorable thing to do was to pay all of his investors back, which he did. The $96,600 he wrote off on his taxes in 1973 and 1974 was part of those repayments. Twitty and his lawyers argued that if he didn’t repay his debts, it could be detrimental to Twitty’s reputation as a country music singer. That is why it should be permissible to be written off under his entertainment earnings. Remember, Conway was already on shaky ground with some in country music since he’d started on rock n’ roll.

“It was the morally right thing to do,” Twitty insisted. “They put their money in Conway Twitty, and Conway Twitty did it all wrong – that’s why I paid them back.”

The IRS disagreed, saying losses from Twitty Burger had nothing to do with country music. So the matter went to court in 1982. What was the result? Conway Twitty won. In 1983, the U.S. Tax court determined that the personal image of country music artists are vital to their careers, and that Conway was in the right to declare the losses to protect his personal reputation. Quotes from country music historians explaining the importance of character and honesty in country music were considered by the court in the case.

“We’re fighting over $100,000,” said William Whatley, Conway Twitty’s attorney at the time. “Conway could make that much money in the first three minutes of a concert. It’s the principal that counts.”

Though it’s only an interesting snippet of country music history, the case known officially as Jenkins vs. Commissioner is much more significant when it comes to tax matters. The case is still cited as relevant case law even today in how entertainers can declare business expenses on their taxes, and how reputation can factor into those decisions.

And this isn’t the only lasting contribution from the case. In an unprecedented move, the court, after deciding in favor of the country legend, rendered their ruling partly in a song called “Ode To Conway Twitty.” It goes:

Twitty Burger went belly up

But Conway remained true

He repaid his investors, one and all

It was the moral thing to do.

His fans would not have liked it

It could have hurt his fame

Had any investors sued him

Like Merle Haggard or Sonny James.

When it was time to file taxes

Conway thought what he would do

Was deduct those payments as a business expense

Under section one-sixty-two.

In order to allow these deductions

Goes the argument of the Commissioner

The payments must be ordinary and necessary

To a business of the petitioner.

Had Conway not repaid the investors

His career would have been under cloud,

Under the unique facts of this case

Held: The deductions are allowed.

– – – – – – – –

In 1984, when the IRS decided not to appeal the court’s decision, they responded in kind, saying:

Harold Jenkins and Conway Twitty

They are both the same

But one was born

The other achieved fame.

The man is talented

And has many a friend

They opened a restaurant

His name he did lend.

They are two different things

Making burgers and song

The business went sour

It didn’t take long.

He repaid his friends

Why did he act

Was it business or friendship

Which is fact?

Business the court held

It’s deductible they feel

We disagree with the answer

But, let’s not appeal.

Yes, the Jenkins vs. Commissioner case holds as tax law even today, but the legal outcome that would befall Conway’s Twitty City was not as advantageous for keeping the Conway Twitty legacy alive into the future.

Conway Twitty died unexpectedly of an abdominal aortic aneurysm on June 5th, 1993. He was 59 years old. The day before his passing he’d been performing in Branson, Missouri when he fell ill during the show. Twitty eventually collapsed on his tour bus, and the driver Bill Parks drove him to the Cox South Hospital in Springfield, Missouri where emergency surgery was performed. But doctors knew it was unlikely he would pull through, and the call was put out for his family to come to his side.

Completely by chance, when Conway Twitty arrived at the hospital in Springfield, Loretta Lynn was at the same hospital tending to her husband Doolittle who was suffering from complications with diabetes and was gravely ill himself.

“When they brought Conway in I couldn’t believe it,” Lynn told Ralph Emery in an interview some years later. “I just could not believe it. It was the worst thing I’ve ever been through really. I stayed with Dee (Conway’s wife) and I stayed with the band for a while, and then I’d run up to see Doo, and then I’d run back to sit with Dee. And then I’d run back to see how Doo was, because he was in real bad shape. They thought he was going to die any time. I was in bad shape myself.”

Also at the hospital with Conway Twitty’s third wife Dee were Conway’s adult children Michael, Joni, Kathy, and Jimmy. They were all there together about an hour before Conway died. Loretta Lynn was by Doolittle’s side when she heard the news.

What transpired in the aftermath of Conway Twitty’s death was one of the most tumultuous estate battles in country music history, with Conway’s $15 million-dollar estate, the fate of Twitty City, as well as the fate of all of Conway’s possessions and the control of his music becoming embroiled in the bitter legal battle that would drag on for 15 years.

Conway Twitty was married to Ellen Mathews between 1953 and 1954. The two had married due to Ellen’s pregnancy with son Michael, but the marriage didn’t last long after the birth. Conway married his second wife Mickey in 1956, and they stayed married until 1984 aside from briefly divorcing in 1970. This marriage is where Conway’s children Kathy, Joni, and Jimmy come from. Conway married his 36-year-old office secretary in 1987— Delores “Dee” Henry—but never amended his will after the marriage. This is what led to the estate conflict.

Conway Twitty’s will and testament left everything to his four children, and didn’t even mention Dee, who at the time had become a significant part of his music business, including accompanying him on tours, and helping to produce music. But Tennessee law required Dee to receive at least a third of Conway’s estate as his spouse, throwing the whole will into dispute, as well as the fate of Twitty City.

Twitty City was constructed as the private home for Conway Twitty, his family, and to secure his legacy for future generations. It included a house for Conway’s mother, a house for each of his four adult children, as well as a 24-room mansion for himself and his second wife Mickey. There were also elaborate gardens, an extensive gift shop, at at Christmas, one of the biggest Christmas light displays in the South.

The idea behind Twitty City is that family would be together forevermore, and even after Conway Twitty passed, it would live on as a testament to his legacy, and to house the artifacts of his life. Conway’s four children also worked there, running the gift shop, giving tours, and performing other duties for annual salaries.

“I built Twitty City because I wanted to have a place where my kids and I could always be close together, and they have homes right here,” Conway explained in an episode of ‘Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous’ from the 80’s. “I also wanted a first-class place for country music fans to come to when they come to Nashville, and get as close to an artist as they can get. A lot of my friends in this business said ‘Conway, you’ve lost your mind.’ And I can understand how they feel, but they haven’t been as close to this concept as I have. I have all the privacy I need right here at Twitty City. I can come out my door and get to my office which is only 100 yards away if I want to without anybody ever seeing me. Or if I want to be seen, I can.”

But this strange public/private nature of Twitty City is said to have been what led to trouble between Conway and his second wife Mickey. She didn’t want fans constantly around her home. Something else Conway’s friends and family point to that caused friction in his marrige and elsewhere was an incident in 1981 when the country singer slipped and fell on the steps of his tour bus, hitting his head violently. After the fall, apparently Twitty’s personality took a dramatic shift and he never acted the same afterwards, or like his true self. He would forget to finish sentences, or would pick up a TV remote thinking it was a telephone.

Conway’s children didn’t exactly approve of Conway’s marriage to the much younger Dee in 1987, but they learned to live with it when Conway was still alive. But after his death, the executors of Conway’s estate shut off the children from the regular salaries they were receiving from their father and Twitty City for doing various tasks around the complex. The executors also hired Dee to be a consultant for how to handle Conway’s musical affairs after his death since she already was so deep in his affairs, further isolating his family from the process.

Conway Twitty’s children then tried to remove the will’s executors, but the probate court struck the motion down. Frustrated by the court’s decision, Conway’s daughter Kathy then went to the local newspaper, The Tennessean, to tell her story about how the heirs of Conway Twitty were getting locked out of the process by Dee and the executors, and how Dee had made out with the $1.8 million home she shared with Conway, and another $900,000 in life insurance after Conway’s passing before getting her third of the estate.

After the newspaper report, the entire process boiled over with animosity between the respective parties. Angry about the article, Dee demanded that the entire estate be liquidated so it could be split up equitably between the respective parties. In June of 1994, a Tennessee probate court agreed, and ordered the full liquidation of the entire Conway Twitty estate, including Twitty City, all artifacts and memorabilia, musical instruments and trophies, even down to the family’s baby photos and love letters between Conway and his second wife Mickey.

Once again, the executors of the will hired Dee to be the party to catalog all of Conway Twitty’s assets and get them ready for sale. One day when Conway’s daughters Kathy and Joni witnessed Dee and others loading boxes into her trunk from the Twitty City office, they confronted Dee and the executors asking them what was going on. The situation turned heated, and a judge issued a restraining order, barring Conway’s heirs from the property.

Eventually, all of Conway’s children and his 81-year-old elderly mother were told they most move off the property by August of 1994. While still grieving the death of their father, and amid a bitter estate dispute, Conway’s children had to uproot themselves from homes they believed they would be in forever and together as a family, and find new places to live. Twitty’s mother passed away two months later, with Conway’s children claiming the stress contributed to her passing. The Twitty City property was ultimately sold for $3 million.

Then came the auctioning off of all of the estate items. “It was almost as hard as losing our dad again,” says Conway’s daughter Joni. “These things were a picture of his life. It was a hard day. It felt like daddy dying again.”

Conway Twitty’s second wife Mickey also showed up to the auction, and saw that love letters between her and Conway were part of the items on the auction block. Mickey is quoted as saying, “That’s my mail. How can they sell my mail?” Mickey then grabbed the love letters from behind glass partitions, but police at the auction forced Mickey to return them so they could be auctioned off. The auction of Conway Twitty items lasted three days, and ultimately netted about $1 million dollars. Conway Twitty’s physical legacy had officially become a diaspora.

Then in 1996, Dee and Conway’s children entered into another legal battle. At the time, Conway’s heirs were seeking the medical records for their father, in part to help understand why months after passing a life insurance physical exam and getting the all clear from doctors, he died suddenly of the abdominal aneurysm. Meanwhile, Dee wanted to disinter Conway’s body and cremate it. Part of Dee’s motivation was due to graffiti that appeared on Conway’s grave calling Dee a “bitch” for being so aggressive against Conway’s kids.

Dee may have been winning in court. But in the court of public opinion, Dee was losing demonstrably. The news of Dee’s intention to cremate Conway’s body only made that public perception worse. Amid public backlash against Dee for wanting to disinter Conway, she ultimately dropped her petition with the court for him to be cremated.

The final piece of the Conway Twitty estate to be settled was his intellectual property, namely the control of his music publishing, royalties, as well as his name and likeness rights. After Dee and Conway’s children couldn’t come to agreement on how to share the assets, Dee once again advocated for them to be auctioned and split equally. However, as opposed to auctioning them publicly, the court decided to hold a private auction between Dee and Conway’s children where they will bid between each other for control. Pooling their money from their father’s estate, Conway Twitty’s children eventually cast the winning bid for control over his intellectual property, paying $4.2 million dollars.

Ultimately, the fight over the Conway Twitty Estate by his heirs results in Conway’s daughters Joni and Kathy testifying in front of the Tennessee State legislature about changing the law in the state that immediately rewards the spouse of a deceased individual a third of their estate. Due to the public backlash against what happened to Conway Twitty’s children, the Tennessee Legislature passed what is now known as the Conway Twitty Amendment to the existing state law.

The new amendment takes into account the duration of a marriage in estate proceedings. After Joni and Kathy told the story of what had happened with their father’s estate and Twitty City, lawmakers were reportedly crying, and hugged the two women afterwards, appalled about what had happened.

The law had been changed, but the damage had been done to the Conway Twitty estate, Twitty City, and the memorabilia that told the story of Conway Twitty’s life and career in country music.

As country music journalist and historian Robert Oermann says, “I think the unfortunate thing about the estate battle is that it has in a sense prevented carrying his legacy forward. Because the estate was frozen as it was for so long, it made people kind of forget a little bit, because he wasn’t being brought before the public.”

For the record, Robert Oermann also believes that Dee has gotten a raw deal from the public over the years, that she worked hard to promote Conway’s music in life and after his death, and was put in a difficult situation with the family.

The Trinity Broadcasting Network is who purchased the Twitty City complex itself, turning it into studios and offices for the television company, later calling it Trinity Music City. For some years after, tours of the grounds were still given upon occasion, and tourists could also still request to see Conway’s 24-room mansion. But as Saving Country Music reported in 2016, management finally ceased giving tours of the property.

By 2023, the Conway Twitty home had fallen into disrepair since Trinity Broadcasting wasn’t using it, and had no incentive to maintain it. Then on December 9th, 2023, and EF-2 tornado ripped through the property, further damaging the home. Trinity declared the structure was beyond repair, and planned to demolish it to make room for new improvements on the property. But after a public outcry, In January of 2024, Trinity Broadcasting decided they would restore the home as opposed to demolish it.

Nonetheless, the Conway Twitty legacy in country music still feels like it doesn’t rest in its proper standing. It took until 2021 for many of his previously-unavailable albums to finally be reissued. But the numbers and legacy don’t lie. Conway Twitty was one of the most successful and beloved country music artists of all time.

Sources:

Wilbur Cross: “The Conway Twitty Story: An Authorized Biography“

Reality TV: “The Will: Family Secrets Revealed” – S02 – EP03

Saving Country Music: “Conway Twitty’s Former Twitty City No Longer Giving Tours”

WKRN News 2 – “Conway Twitty’s Hendersonville Home Saved from Demolition“

March 14, 2024 @ 7:48 am

FYI folks, gonna be at Willie Nelson’s Luck Reunion all Thursday, so apologies if comment moderation take a little longer than normal.

Also for folks wondering what happened with the Saving Country Music Roundup Podcast, I will have an update about it soon.

March 14, 2024 @ 8:20 am

These are the kinds of stories I love the most on here. Thanks Trigger!

March 14, 2024 @ 9:18 am

Early Conway music was good. “It’s Only Make Believe,” and “Fifteen Years Ago” are my favorites of his. However, the greatest comment about Conway’s later career was from the late, VERY GREAT Lewis Grizzard, who said, “I want Conway Twitty to take a long, cold shower right before he steps into the recording studio.”

March 15, 2024 @ 5:29 am

Just have to acknowledge the very rarely seen Lewis Grizzard shout out. He has a book called ““If I Ever Get Back to Georgia, I’m Gonna Nail My Feet to the Ground.”. When folks ask if I ever consider moving somewhere else again, I tell ‘em I managed the first part, and sometimes consider the second.

March 14, 2024 @ 10:14 am

Thanks for the shout out

March 14, 2024 @ 10:25 am

You can find Harolds rockabilly sides he recorded at Sun on the expansive Bear family release Conway Twitty- The Rock and Roll Years, including his own take on Rock House. Great stuff, I love his rockabilly as well as his country material. Interestingly, Sam Phillips didn’t get Harolds permission to let Roy Orbison record it. Sam had a limited budget and limited ability to promote his artists, and Orbison was an artist he was trying to market. That song Rock House became the title track to Roy’s first and only album released on Sun, titled Roy Orbison at the Rock House. It’s always been fascinating how many legends of American music initially did recordings at Sun, and many of them Phillips did nothing with, yet they would in time become a big deal. Some examples include Ike Turner, BB King, Howling Wolf, Ed Bruce and of course Harold Jenkins aka Conway.

It’s really staggering when you also consider Phillips discovered, recorded and promoted Johnny Cash, Elvis, Jerry Lee Lewis, Carl Perkins and Charlie Rich and Orbison. Phillips had an ear for talent, to say the least. Amazingly, that list of legends collectively generated millions of dollars throughout their lives, and Phillips got almost none of that pay-off. The money he did manage to earn, he invested in radio stations and some mining.

A few favorites among Twittys lesser hits in my opinion worth checking out: Boogie Grass Band, Saturday Night Special, Your the Reason our Kids are Ugly with Loretta Lynn.

March 14, 2024 @ 2:13 pm

Conway was a great singer and I hate to see his house torn down.

March 14, 2024 @ 2:23 pm

And don’t forget Sam Phillips parlaying the money from selling Elvis’ contract to RCA into the fledgling Holiday Inn chain and recouping his investment many times over.

March 14, 2024 @ 11:29 am

Very interesting artist and huge, in his time.

I don’t think one can blame Conway’s somewhat early death for the diminishment in his reputation because many of the artists whose legacies endure and who keep getting talked up–Patsy Cline, Lefty, and of course Hank and Elvis –died at considerably younger ages than Conway Twitty did.

I think it has more to do with his style. The post-rock-a-billy Conway, in his prime years as a country hitmmaker, comes off as somewhat creepy–as you mentioned–but also dorky to today’s viewers. Apparenly, the “Family Guy” program made a thing of randomly inserting videos of Conway into their hip cartoons, because that was enough to draw cheap laughs from their young viewers. (On Y-T, Conway’s videos are populated by various comments along the lines of “I came here from Family Guy.”)

March 14, 2024 @ 12:25 pm

In the case of Hank, Patsy, Elvis, I think how young they were elevated their legacy. I think it’s these folks that die in their late 50s-early 60s get it the worst. I think in some respects, this happened to Waylon as well, though I think his legacy has risen lately.

But like you said, I do think it also has to do with his music not really fitting well into the modern zeitgeist.

March 14, 2024 @ 12:41 pm

I’d agree that by lasting longer, Willie and Cash and Jones and Dolly all managed to add positive final chapters to their stories. Most country artists–even the ones who live long–don’t get that sort of comeback. That was kind of the theme of Waylon and his 3 compadres on “Old Dogs.”

March 14, 2024 @ 12:43 pm

It’s impossible to say how Conway’s career would have played out post-1993.and, but he simply didn’t have the coolness factor that turned all of the alt rock kids on to Johnny Cash, nor the backstory that made a song like “Choices” compelling enough to put George Jones back in the spotlight. My thought is that his window of opportunity to extend his career past his viability on the mainstream country charts would have been in the ’80s, with a return to the rockabilly realm back when it was having a bit of a revival. As it stands, he died when he was no longer producing his best work and hadn’t yet been offered the right opportunities for a late-career comeback.

March 17, 2024 @ 6:17 pm

I think his style was very of its time. In general he had a lot of ladies man ballads, or a lot of studio gloss that didn’t age well. Definitely made loads of hits in his time. Do other artists really cover his stuff? I hadn’t thought of his work forever till Willie Nelson covered “I don’t know a thing about love” a couple years ago. Always struck me as a good 1 or 2 disc compilation artist with little need to dig farther.

March 14, 2024 @ 12:24 pm

I work in the financial industry. Heirs and money are a volatile situation, especially in second, and beyond, marriages. True character shines, good or bad.

March 14, 2024 @ 3:52 pm

Hmmmm.I thought Conway went to Country because he’d been superseded by others,especially Elvis in rock. It also seemed that Twitty’s good looks had been played down,and he perhaps thought himself more attuned to the Country crowd than the rock and rollers. (Bad management didn’t help.)

I wonder if Twitty hadn’t first gone to baseball,he’d have perhaps rivalled Elvis as a rocker,but I always thought it was his gentleman stud persona was the key to his Country success.RIP,Conway,you were one of the best !!!!!!!

March 14, 2024 @ 4:56 pm

Very interesting article. While I like a lot of Conway Twitty’s songs, I have never delved deep into his catalog. Play Guitar Play is my favorite tune that most don’t know. Another fun fact I read somewhere Conway’s AMC Pacer was his favorite car he ever owned. As an AMC enthusiast makes me appreciate Conway all the more.

March 14, 2024 @ 5:05 pm

The outrage over Conway’s “creepy” tunes always amuses me. Especially in a world where “WAP” is considered acceptable for children.

Conway came from a generation where clever lyrics and imagery conveyed mature topics. A regal sheen on base topics.

I wish he was better remembered. I enjoy his music more than Willie’s and several other legends always name-dropped.

March 14, 2024 @ 8:52 pm

@CK.-I mostly agree with you.

Conway had some songs that were creepy or cloying, by my taste. But he did so many songs of different styles that I can skip by the ones that I don’t like and find a lot of good ones. I loved his treatment of pop or r&b songs in the ’80s like “Slow Hand” and “The Rose”–even though I’ve read that some country fans don’t like those. And “the Man in the Moon Song,” which was reportedly his first hit–or at least first #1–on a Harlan Howard song. And I think he had a gem with what’s either the last–or near he last–recording of his that was ever released: an ad-libbing, talking and signing duet of “Rainy Night in Georgia” with Sam Moore. His early recordings like “It’s Only Make Believe,” of course, and rocked up versions of “Danny Boy” and “Mona Lisa” were also fun.

March 15, 2024 @ 4:28 am

I agree Conway’s songs were certainly suggestive. Songs like WAP that you mentioned are down right vulgar but no one blinks an eye.

March 16, 2024 @ 7:12 am

People always say ‘it’s just like (insert dystopian fiction)” but one commonly referred to is battle for planet of the apes, from which the quote ‘an ape can say ‘no’ to a human but a human can never say ‘no’ to an ape’ is commonly interpreted as a stand-in for another word.

See, in ‘battle’ it follows up from the previous movie, in which humans enslaved circus apes, and the first ape saying ‘no’ to a human started the rebellion.

Why this context from a sequel to a sixty year old movie?

Sci-fi always satirizes present issues. It’s the obvious metaphor it seems to be. (the ‘ape’ part seems self defeating in modern contexts, not that the metaphor intended to imply anyone was more primitive)

But the reason WAP and other songs are ‘fine’ and Conway might be considered creepy ties into a greater social trend, or actually, two competing trends.

See, Some people find that social imbalances are fixed by raising everyone who hasn’t to the level of those who has. take away the exclusivity of language and expression so that people historically unable to take part now can participate.

The other trend is that some people are trying to take the tool of oppression away from the oppressor, holding the users accountable for its use and therefore no one gets to use certain words or certain modes of expression.

Both groups probably have valid points, but to say that ‘WAP is fine but Conway is creepy’ is a mischaracterization of a niche mindset.

the simple fact is that most people have nuanced opinions on complex social issues but their personal histories and life experiences bias them towards some suspended disbeliefs. Women who struggled to be heard and find expression might find WAP liberating, and women who overcame inattentive parents and developed interpersonal skills and found successful family lives might find it self-defeating.

From a certain point of view, both are right.

As for Conway

Conway being ‘creepy’ is just a sign of social trends.

Mysterious men are out right now.

John Wayne archetypes who swallow their feelings and saddle up and persevere are out right now.

Men who are sincere, open and sensitive are in right now. vulnerable men are in.

mysterious, performative men are now taken as shallow, vain and narcissistic.

And in another few years the trend will change again.

March 16, 2024 @ 12:14 pm

The perceived creepiness had to do with the poorly-masked come-on (Who does he thing he’s fooling?) (and also because Conway seemed to be an already middle-aged man hitting on younger girls).

I think Jimmy Buffet captured it a the time with the hilarious “Why Don’t We Get Drunk and Screw?”

March 14, 2024 @ 6:07 pm

Interesting article. I never heard about the tax law or the Conway Twitty Amendment.

I

March 14, 2024 @ 6:28 pm

When the rest of his Decca albums going to be available for digital download?

March 16, 2024 @ 2:43 pm

Decca was absorbed into MCA in 1972. Most of MCA’s masters went up in the Universal storage facility fire. Your guess is as good as mine.

March 14, 2024 @ 8:03 pm

“After Joni and Kathy told the story of what had happened with their father’s estate and Twitty City, lawmakers were reportedly crying, and hugged the two women afterwards, appalled about what had happened.”

I laughed out loud at this. I highly doubt the “lawmakers” were crying. Dee deserved her share of the estate, she was Twitty’s wife, regardless of what her kids or anyone else thought. Conway not amending his will caused the problems with his estate.

I took my dad, a fan of Conway’s, to Twitty City not long before it closed. It was lame and so outdated.

March 14, 2024 @ 9:16 pm

A great read. Thank you. Loved it.

It was always a wonder to me why the award shows were not friendly with Conway unless he was with Loretta. Now I understand a few views of why. Loretta and Conway were untouchable in the duet realm for 4-5 years, and I have always wondered why it did not translate to Conway’s solo status.

March 15, 2024 @ 4:26 am

…what a legend, perhaps not in architecture though.

March 15, 2024 @ 4:54 am

A similar case may be said about Sonny James. Between 1967 -1971, every song he placed on the chart went to #1 for a total of a staggering 16 #1 hits. While he had more #1’s before and after this time, it did set a record that would not be broken until Alabama came around in the 80’s(the debate continues if “Christmas in Dixie” should be considered as a steak breaker or not being a Christmas Song). Regardless, it still set up his career as a certified hit maker. Sadly, his legacy on country radio is largely ignored and forgotten despite being an absolute major hit maker in his day. Conway was the king of the charts stretching in to 5 decades. He would score one final minor hit with the Frankensteined collaboration with Anita Cochran in 2004. He also collaborated with Dean Martin in 1983 and released a song appropriately called “My First Country Song” (although Dean himself did record several other country songs over his career). Conway will always be considered a titan in the industry, and his music will endure. If he can draw in people from Family Guy who genuinely come to appreciate his music then it is a given Conway has earned his place in Country. He even gets a mention in the George Jones song “Who’s Gonna Fill Their Shoes?” It was sad to learn of all of the legal issues with his family. Money can bring out the worst in people.

March 15, 2024 @ 8:37 am

I mentioned Sonny James before as an example of how a legacy can be a tricky mistress. James’ streak, IIRC, was mostly powered by covers. Which might explain why he fell into obscurity.

This site ranks every year’s #1 songs on the country charts. It is fascinating how many names are virtually unknown now or how a legend’s #1 is rarely considered popular.

https://heartachenumberone.blogspot.com/

March 15, 2024 @ 12:36 pm

Loved Conway’s music. Why he isn’t talked about more, hard to say. Probably cause he was never an outlaw type figure and he didn’t live long enough to get the cool factor bit like cash did. Doesn’t really matter though, he had a fine career. Got to earn a living doing something he loved, most don’t get that. His music being creepy is kind of nonsense to me. Not with the music kids are listening to or being exposed to today.

March 15, 2024 @ 1:04 pm

Great article, and useful for a lot of us who are Conway fans but don’t really know all that much about his life. Despite all the hits, aside from his “ladies’ man” persona (which some people treated like more of a joke or liability) he didn’t have a mythos about him like Cash, Haggard, Waylon etc. Plus he wasn’t as obvious of an influence on the ’90s country folks as Haggard & Jones, when a lot of folks were trying to stress their “hard country” bona fides. But Twitty had some great old-school country songs himself even if he wasn’t shy about working in pop or R&B influences in search of a hit.

He might’ve had a lame song here and there (“I Was The First” … ick, man) but the good outweighs the bad by so much. Awesome, dramatically gifted voice and good taste in material for the most part. Maybe it’s the name, maybe it’s the hair, maybe it’s the sex songs that make some folks a bit uncomfortable, but I do think it’s too bad he’s seen as a bit of an ironic joke sometimes (like the Family Guy bits, or how the main characters in Righteous Gemstones and Dewey Cox eventually look so much like him it’s probably not an accident). I guess that’s better than just being forgotten, but I think his legacy deserves more.

March 16, 2024 @ 5:51 am

MEM,

Love the site. It deserves more comments. I will have to remedy that. One of the best country music sites around.

March 16, 2024 @ 8:09 am

Thanks very much, glad you dig it.

March 17, 2024 @ 7:01 am

No joke here. Just checked the site out and after reading the comment comparing Colin Rayes “Love, Me” as the musical equivalent of of watching the first ten minutes of “Up”, you’ve gained a reader for life…

Back to Conway, though. I’m generally not overly emotional but his song “That’s My Job” always tugs at my heartstrings.

Trigger, great article here. I know journalism is a hard slog for a career but this is a worthy endeavor that not everyone could do. Thank you.

March 15, 2024 @ 7:00 pm

Let this be a lesson. If you get divorced or marry someone new, immediately review your will and the beneficiary designation on any life insurance, retirement accounts, and “payable on death” CDs or other accounts. People forget, and the hated ex may get lots of stuff, or with an odd law the brand new bride may clean up when that may not have been the intent of the deceased.

March 15, 2024 @ 7:25 pm

Great article. Thank you. His music was consistently excellent from start to finish because he evolved his style and song choices over the years. No, I don’t find anything creepy about him or his songs. He had a reputation as a decent human being.

It’s a travesty his family squabbles have overshadowed his legacy to the point where many country fans know Conway more for the legal battles than his music. His daughters run a Facebook page and I have to be honest: they (particularly Kathy) come across as bitter and and vindictive and 30 years later still put down his widow as well as their half brother who they don’t like. I know none of these people nor do I know what really happened, but from an outsider’s perspective it seems really odd to keep fighting the battle in such a public way and keeping the drama alive as opposed to his music.

March 16, 2024 @ 8:19 am

My step daughter Joyce baby sat for Conways Daughter Joanie when he moved to Oklahoma, city and started singing country music.

March 18, 2024 @ 2:11 pm

Thanks for nailing the tax facts. I’m a long-time tax CPA and have been aware of the case for decades. The case by itself is a testimony to the immense character of Harold Jenkins.

I was at Buffet concert way back and Jimmy actually name checked Conway Twitty as the major influence for “Let’s Get Drunk and Screw”. As I recall, Jimmy noted he was tired of dancing around the message and decided to get to the point.

March 18, 2024 @ 4:31 pm

Going to be honest, never liked Conway. Ironic as Loretta’s always been #1 with me, but since I was little he gave me the creeps. I do appreciate Hello Darlin’ and, although it’s not Country, It’s Only Make Believe. I remember seeing the estate fight on that show the Will. Horrible. And I recall there being an incident at one of the award shows shortly after his death because the kids weren’t invited (or Dee wasn’t?). Sadly, Dee, Nancy Jones, and George Ritchey are all the same. Rotten. I had hoped George would’ve learned from what happened with Tammy and Conway. I do take exception to a few of the Elvis comparisons…not on Twitty’s best day, not even close. I do hope Twitty City is successfully restored and preserved though. But even more so Loretta’s first partner’s physical legacy in it’s original form, ET’s Record Shop ❤️

March 19, 2024 @ 3:11 am

Thank you Trigger for posting the recipe snapshot

Of the Twitty Burger. Anyone out there adventurous enough to cook try it out?

March 19, 2024 @ 7:15 am

D. Striker made one a while back:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6L8JIiMovEc&t=91s

March 19, 2024 @ 2:43 pm

What was done to his family after his death was unconscionable. For Mr. Oermann to say the last Mrs. got a “raw deal”, given what she ended up with, is unbelievable. One would think Conway’s business manager, attorney—someone!—would have pressed for his will to be updated and details clearly spelled out after the last “I do”. He was a monumental talent; an all all-around gifted entertainer.

March 20, 2024 @ 4:21 am

Conway is on country’s Mount Rushmore and anyone who disagrees can eat concrete powder and drink a glass of water

April 11, 2024 @ 7:25 pm

I think Dee couldn’t have loved Conway as much as she says or she would have done as Conway wanted that his Mother and his four children remain in their respective homes. Furthermore, Executors shouldn’t have hired Dee as that was a certainly conflict of interest. You would have thought their home, life insurance and all she attained while married to him could have satisfied her. I have no use for her because of her actions toward his certainly.