Beyoncé Songs Spur False Claims Country Music Erased its Black History

In 2024, country music is celebrating the 50th Anniversary of what many consider to be the genre’s most important artifact, and one that appraisers cite as the most valuable asset sitting in the Country Music Hall of Fame’s possession in Nashville.

No, it’s not the guitar of Hank Williams, or the mandolin of Bill Monroe, or the banjo of Earl Scruggs. It’s a painting of all things, called “The Sources of Country Music.” Commissioned by the Country Music Association, or CMA in 1973, and painted by legendary American artist Thomas Hart Benton, it was meant to become the crown jewel of the CMA’s Hall of Fame collection, and has since become that very thing. The painting hangs as the centerpiece and the first thing you see as you enter the Hall of Fame rotunda where the plaques of all the official inductees adorn the walls.

Near the end of 2023, the Hall of Fame opened a new exhibit called An American Masterwork: Thomas Hart Benton’s “Sources of Country Music” at 50, which explores how Benton developed his final painting, through sketches and drawings, lithographs, photographs, a three-dimensional model of the painting, and video footage of Benton.

This painting is critically important to the history of country music because it offers a time capsule that no revisionist history can touch. The painting is made to depict the various origins of country music, including the Western cowboy of the silver screen era, a Gospel choir, old-time fiddlers and singing sisters, square dancers, as well as a locomotive, a steamboat, and river in the background.

One aspect about the painting that is most important is the inclusion of the African American character playing a banjo. For Thomas Benton and the Hall of Fame, there was never any question that the Black influence in country music must be included in any portrayal of the genre’s origins.

In fact, one of the often-overlooked features of the painting even by many historians and interpreters of the work are four more African Americans just over the shoulder of the black banjo player. They are standing on the shore of the river, with their hands outstretched towards the steamboat.

If you want to learn more about the fascinating story of what became Thomas Hart Benton’s final paining, you can find a more detailed account on Saving Country Music’s Country History X episode about it.

What’s so important about this painting is not just it’s current anniversary. It’s that it offers a strong counter-argument to one of the most unfortunate social contagions surrounding Beyoncé releasing a couple of songs being characterized as country ahead of what’s anticipated to be a country album (read more).

Using this current event as a jumping off point, numerous outlets and now viral social media posts have proclaimed that the Black influence and contributions to country music have been stricken from the history of the genre. This has resulted in perhaps the greatest eradication and wallpapering over of the Black legacy in country music that the genre has ever experienced.

The “Sources of Country Music” painting commissioned by the founders of the CMA is one obvious and indisputable illustration of how the Black influence in country was not whitewashed. But this is not the only one by far. In fact, out of the nearly two dozen general history books on country music sitting on the shelf at Saving Country Music headquarters, none of them claim that Black creators did not have a hand in the formation of the genre. On the contrary, every single one of them state that Black creators were critical to country’s formation.

This also extends to biographies in the Saving Country Music catalog, from multiple biographies on Hank Williams that credit Black blues performer Rufus “Tee-Tot” Payne as the man who taught Hank how to play the guitar, to the Waylon Jennings autobiography where he explains how he would “cross the tracks” when growing up to listen to Black music and later used that influence in his Outlaw country style, and even got fired as a DJ for playing Little Richard.

The Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum in Nashville is considered one of the greatest music history museums in the world. In both public-facing displays and in the museum’s 2006 350-page companion book written by country historians Paul Kingsbury and Alana Nash called Will The Circle Be Unbroken, it states expressly:

Black and whites had met and mingled since the early Colonial era, absorbing much from each other across a racial barrier that held firm socially but remained porous culturally. In many ways, poor blacks and poor whites shared a folk culture with a common body of songs, dances, and instruments that moved freely across racial lines.

Black fiddlers were ubiquitous in the 19th-century South and, in fact, were described much more often than white musicians in the newspapers, travel accounts, and other literature at the time. Slaves frequently attended religious revivals in the antebellum era, and while they were typically segregated from white worshipers, their singing was recognized and admired nevertheless.

…White musicians did not simply learn from blacks to sing more expressively, with full, open-throated emotion; they were inspired also to take up new instruments, such as the banjo, and to experiment with unorthodox chord progressions, blue notes, slide-guitar techniques, and unusual rhythms.

Throughout Will The Circle Be Unbroken and the Country Music Hall of Fame itself, there are countless citations and segments of presented history that speak to the Black influence in country music. This inclusion of Black performers also extends into current exhibits like the American Currents exhibit for 2024 that features Joy Oladokun, Allison Russell, and SistaStrings.

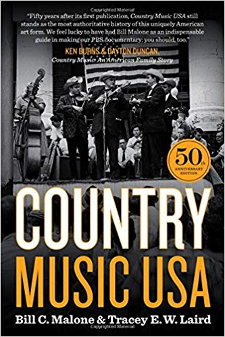

The book that is considered the defining history on country music and is regularly used to create college course work is Bill C. Malone’s Country Music USA. This book plays a critical role in defining country history because it is commonly cited in other country histories and is considered the most definitive. Country Music USA was also used as the source material for the Ken Burns-produced 8-part PBS documentary Country Music that aired in 2019.

Country Music USA is a dense, 700+ page tome of country music. Five pages into the history, Bill C. Malone states:

Of all the southern ethnic groups, none has played a more important role in providing songs and styles for the white country musician than the forced migrant from Africa, the black. Nowhere is this peculiar love-hate relationship that has prevailed among the southern races more evidenced than in country music. Country music—seemingly the most “pure white” of all American musical forms—has borrowed heavily from African Americans. White southerners, many of whom would have been horrified at the idea of mixing socially with blacks, have nonetheless enthusiastically accepted their musical offerings: the spirituals, the blues, ragtime, jazz, rhythm-and-blues, hip-hop, and a whole host of dance steps, vocal shadings, and instrumental techniques.

Black-white contact began so early and was so omnipresent in American life that it is virtually impossible to know who profited most from the musical exchange. From the time they first saw them on slave ships, white observers have commented frequently on blacks’ alleged penchant for music. In the four hundred years that have passed, white musicians have continually drawn on black sources for rejuvenation and sustenance.

And this is just the very start. Reams upon reams of the history are devoted to Black minstrel players, the Black origins of the banjo, White performers performing as blackface minstrels, and other topics centered around country’s Black influence in the book. In fact, one regular refrain you read in most any country history book, including Country Music USA, is how the Black influence on country music is often misunderstood by the public, but elemental enough to be indisputable.

The First Edition of Country Music USA was released in 1968. In 2018 ahead of the new Ken Burns documentary series based off the book, a 50th Anniversary Edition was released.

It’s not just that country music’s Black influence is clearly laid out in history book after history book. It’s that in country music’s most defining history book and one of its best selling ones, Beyoncé and her influence is actually talked about in detail. That’s right, six years ago, and six years before Beyoncé would choose to make a country album, she was already cemented in the annals of country’s written history.

For the 50th Anniversary edition of Country Music USA, Bill C. Malone allowed Tracey E. W. Laird to compose the 13th and final chapter. A professor of music at Agnes Scott College in Atlanta, the new chapter was supposed to pick up where the last edition of the book left off in the year 2000.

But instead of offering any sort of traditional history on the 18 years that had passed since the previous edition—broaching critical moments such as the emergence of Taylor Swift, Bro-Country, the rise of Chris Stapleton and independent artists—Tracey Laird instead rather controversially decided to use Beyoncé’s performance with the [Dixie] Chicks at the 50th Annual CMA Awards in 2016 to set the narrative and bookend the entire chapter, expressly for the rich narratives involving race, gender, and genre this new chapter desired to broach.

Country Music USA‘s Chapter 13 isn’t a history at all. It’s basically a journalistic think piece, or perhaps an academic paper about country music and race imposed as a chapter in a history book. However, one byproduct of this unusual addition to an otherwise sometimes frustratingly dry recitation of country history is that it means that not just Black country history is present in country’s most important history book, Beyoncé is actually already in there.

“What did it mean the the new century’s most sensational pop music performer, an African American woman, to appear on the CMA Awards, a context still so closely associated with whiteness?” the book asks. “Despite historical, artistic evidence of the deeply tangled roots of ‘hillbilly’ and ‘race’ music, as it was christened in the beginning, whiteness continues to define country music. Still, black artists challenge that organically with their oeuvre and repertoire … Nevertheless, whiteness continues to remain a defining trait at the center of twenty-first-century country music identity.”

Why do none of the recent articles on Beyoncé and the expulsion of Black history from country music cite this final chapter in Country Music USA? It’s because the authors of this misinformation have never read it. In fact, it’s unlikely they have ever read any dry, standard country history of any sort. That is how they can falsely convey to their readers the dangerous and irresponsible canard that “country music” erased the Black influence and accomplishments out of country’s history due to white supremacy.

This is what a tweet from Rolling Stone emphasized right after Beyoncé’s first two “country” songs were released, quoting Rhiannon Giddens, who appears on the Beyoncé track “Texas Hold “Em” on banjo and viola. Taken from a 2020 feature, Rihannon Giddens is highlighted in the tweet that went mega-viral saying, “The idea of what country music is has been carefully constructed to seem like it was always white. It was constructed by numerous people as part of the white-supremacy movement.”

But this seems like a strange thing for Rhiannon Giddens to assert. Not only do all of country music major histories expressly state the significant Black influence on country, Rhiannon Giddens has actively participated in the telling of country’s history. Giddens was one of the primary subjects interviewed for the PBS Ken Burns Country Music documentary that aired in 2019, written with the 50-year-old Country Music USA as the source material.

A companion written and illustrative history book accompanied the massive 8-part Ken Burns documentary called Country Music: An Illustrated History, composed by Ken’s co-creator on the series Dayton Duncan. When you open the massive 500-page book, the first illustration you see after the Table of Contents is Rhiannon Giddens playing a banjo in an image from 2010. It’s opposite a quote by Black musician Wynton Marsalis. Giddens is also quoted multiple times in the book.

Note that the Giddens quote from Rolling Stone appeared a year after she appeared in the Ken Burns documentary and the companion book, both of which were lauded by critics, and specifically praised for setting the record straight about African American involvement in country music. Giddens said herself, “It’s a hard needle to move. It really is. The narrative of where people think country music comes from has been really reinforced in very strong ways for very specific reasons. But if anybody can challenge it, it’s Ken Burns.”

Along with Bill C. Malone’s Country Music USA, the Ken Burns documentary is one of the most definitive, and one of the most viewed and cited works on country music history ever assembled. Not only is the Black legacy of country music spelled out expressly in the 8-part film, Rhiannon Giddens was one of the individuals spelling it out specifically.

Countless other examples of country history giving credit to Black creators could be cited here. But just to underscore the point, let’s look at the case of country music’s shortest history. Richard Carlin’s Country Music: A Very Short Introduction released by the Oxford Press is a tiny, pocket-sized history of country music. Would it take the time with such limited space to talk about country music’s Black history? It certainly does.

“Think of country music as a river: flowing along from a starting point in the distinctly American marriage of European and African American musical cultures; meandering through different regions…” it says in the book’s introduction.

The book has a chapter called, “African American traditions: Work songs, Religious music, and blues.” The book also specifically addresses the origins of the banjo, stating, “The five-string banjo developed in the mid-nineteenth century and probably derived from earlier West African instruments.”

And believe it or not, the tiny, small format 100-page Country Music: A Very Short Introduction also includes Beyoncé. On the next to the final page of the miniature history it states,

“Perhaps the biggest indication that pop and country are becoming increasingly one and the same was the appearance of Beyoncé at the Country Music Awards in 2016, where she performed her song ‘Daddy Lessons,’ accompanied by the [Dixie] Chicks. Country diehards were scandalized, but the mainstream country audience accepted this performance as just one more expression on the spectrum of what can be called ‘country music.'”

Wise, prescient words written in a country music history book, copyright 2018.

So why over the last few days after the release of Beyoncé’s songs have we seen this constant reaffirmation that the Black legacy of country music was stripped from history, despite the Thomas Hart Benton “Sources of Country Music” painting, despite every relevant history book putting the Black influence in country in context, and despite the Ken Burns documentary underscoring it to an audience of millions, and in recent memory?

The first is sheer ignorance. Many of the sources for this false information are not native to country music. They are journalists specializing in hip-hop, academics specializing in race issues, or general activists looking to get traction and sow clout on social media by making baseless, and often breathless, hyperbolic claims with no material basis in truth. There is also now a host of books in print that start with the initial premise that country music has erased its Black history, without ever citing any examples.

What is true—and can’t be overlooked—is that there is a general prevailing notion in the overall American population that country music is predominantly a genre performed and enjoyed by White people, both in the past and in the present tense. This is due to most country performers being White, though of course there have been exceptions to that rule ever since the very beginnings of the genre.

But when it comes to the historical literature on country music, this accusation that country removed it’s Black history is patently and verifiably false. In fact, it is these false accusations that are actively erasing country music’s Black legacy in the present tense.

A lot of the misnomers about country music’s origins and influences can be traced through the lineage of the banjo. “The banjo is a Black instrument” is a common refrain you see in think pieces, historical revisionism, and articles surrounding country music and race. It’s most always presented as an “ah-ha!” moment by the author to the audience. But in reality, what the assertion often illustrates is the previous ignorance of the speaker as opposed to the account of the banjo’s origins in the historical record.

For example, the book Country Music USA states, “The banjo’s identification as a rural white instrument is rather curious, since its ‘ancestor’ arrived in this country from Africa and was long associated with slaves. Its earliest appearance cannot be documented, but the instrument that Thomas Jefferson referred to in 1781 as a ‘banjar’ resembled the gourdlike device found much earlier in West Africa. Blackface minstrels introduced their modified version of the banjo to an international public in the three decades before the Civil War.”

As many of country’s histories also explain, in the 1800’s and the early 1900’s, the banjo was categorically considered a Black instrument. It was part of Black stereotyping in advertising copy, and offensive “lawn jockey” yard art and other memorabilia, often in caricaturist portrayals of Black people. Blacks were synonymous with the banjo, so much so that if White performers wanted to play the banjo, they often did so in blackface to attempt to come across as more authentic.

Where did the disconnect between the banjo’s Black origins and it’s misunderstanding as a white instrument originate? Though Rhiannon Giddens and other attribute white supremacy, it’s likely due to two significant cultural moments that became synonymous with the banjo in the 1970s: The theme for the TV show The Beverley Hillbillies played by Earl Scruggs, and the “dueling banjo” scene from the 1972 film Deliverance.

Both of these iconic moments of American culture went to shift the perception of the banjo as an artifact of African American culture, to one of poor, uneducated, slack jawed and incestuous agrarian Whites—not exactly the portrayal those focused on white supremacy may want White culture to be identified with.

The Earl Scruggs style of banjo playing revolutionized the instrument, brought it forth as more of a lead instrument out front in the mix, and dramatically popularized it. This helped obfuscate the instrument’s Black origins, but doesn’t carry any signifyers of white supremacy as part of that transition of thought.

– – – – – – – –

Again, the examples of the Black origins of country music being put in their proper context are quite numerous. One could also cite the work of Hank Williams Jr.

There are the numerous songs from Hank Williams Jr. where he pays homage to his father’s mentor, Rufus “Tee-Tot” Payne, most notably the “Tee-Tot Song.” There is an obelisk and plaque in front of the segregated cemetery in Montgomery, Alabama where Tee-Tot is buried that Hank Jr. and members of the Grand Ole Opry paid for and placed.

To read more about the honoring of Rufus “Tee-Tot” Payne in Montgomery, CLICK HERE.

These days, most of country music history is told online. And online, the amount of think piece and editorial copy canonizing Black participation in country music is outright incredible. But if this material claims that Black participation was stricken from the country music record, it is patently false. This never happened, and despite some attempts to say otherwise, it is inarguable.

– – – – – – – – – –

On February 14th, a hip-hop writer named Taylor Crumpton published an article in TIME titled, “Beyoncé Has Always Been Country.”

The first line of the article states, “The greatest lie country music ever told was convincing the world that it is white.”

This sentence is a verifiable lie in itself. First, country music is not a monolith, meaning that it is made up of various entities, including performers, instrumentalists, songwriters, record labels, radio DJs, festivals, journalists, etc., including many that are Black and Brown. Yet country music is regularly dealt with as if one decision or action represents the entirety of the genre. This is used to indict the entire institution in an irresponsible manner.

But as has been laid out in this article, the history of country music is starkly clear about the importance of Black performers and creators, and has been from the very beginning. That’s not to say that Black performers have been given equal opportunity, equal representation, and have been dealt with equitably over the years because of course they haven’t been. Racism has been prevalent throughout country music’s history. This goes without saying.

But Black performers and the Black influence have been present as well, and irrefutably documented in the genre’s historical canon, including Beyoncé. The fact that Black creators have struggled so mightily is the reason to emphasize their accomplishments if nothing else—to lift them up as opposed to downplaying them as meaningless or tokenary, or eradicating them entirely by saying they were removed from country’s history instead of pointing people to where they exist.

Saving Country Music reached out to the Time author Taylor Crumpton on X/Twiter and asked, “Can you please cite the source of when ‘country music’ told or convinced the world that it was only White? The history book that says this? The documentary? The public speech? Any sort of quote or notation from any authoritative source? Asking in good faith. Thanks!”

Taylor Crumpton promptly blocked the Saving Country music X/Twitter account. There is no discussion to be had about these critical topics, apparently.

The Time article also states, “The truth is that country music has never been white. Country music is Black. Country music is Mexican. Country music is Indigenous.”

In the current media environment, to gain attention for your think piece or tweet, you must ratchet up the rhetoric, be more hyperbolic and radical to separate yourself from the norms, and to flank your peers in the marketplace of ideas. The more radical your statements are, the more they will trend on social media, creating a perverse incentive tugging journalists and activists further towards outright lies.

In truth, the racist revisionism that is happening in country music is the removal of the agency of White performers in the music as being nothing more than trivial appropriators as opposed to contributors. Articles like the Time Magazine piece also strike down huge swaths of country music’s Black history by acting likeit never existed, and simply citing book titles as opposed to delving into deeper discussion these books broach by using direct quotes. It’s sloganeering, not sincere journalism.

In 1971, Charley Pride won the CMA’s Entertainer of the Year Awards, country music’s highest honor. In 2023, Tracy Chapman won the CMA’s Song of the Year and Single of the Year for “Fast Car.” Simply mentioning these achievements in a discussion about race and country music goes a long way in making sure those accomplishments don’t go undermined or ignored.

Ironically, over the last couple of days you have seen White rednecks with “MAGA” in their bios countering Black activist journalists, saying that they are the ones erasing the legacy of Black creators such as Charley Pride, tweeting in all caps “He had THIRTY #1’s!” and the activists responding that those #1 didn’t matter. There is an active effort to destroy all of country music’s Black history to offer a clean slate for Queen Bey to “reclaim” country music for Black people.

But instead of eradicating racism or setting the record strait about country music’s Black history, the effect will be the exact opposite. It will exacerbate the culture war and stoke racism in country music directly. And if you do as Saving Country Music has done here—which is attempt to re-instill Black contributions back into country music’s historical narrative—you will be the one labeled as racist.

– – – – – – – –

You may not think that a single Black guy playing a banjo in a 50 year old painting, and four Black people over his shoulder that you can barely see in online renderings is not nearly enough to set the proper context for the Black contributions to country music. But what is inescapable is that they are there, and they were put the by the CMA’s and Country Music Hall of Fame’s founding fathers. They knew that in the future, someone might try to erase a certain element of country music’s rich tapestry of influences. And so they ensured it never would be.

Try as they may, the Sources of Country Music painting and country music’s primary history books will forever tell the true story. And that story includes critically important Black contributions.

February 15, 2024 @ 12:52 pm

A couple of other things I want to say:

Before I started Saving Country Music, I knew I needed to be boned up on the genre’s history before I ever attempted to speak about it with any authority. So I bought a bunch of books. I bought Bill C. Malone’s “Country Music USA.” I bought “Will The Circle Be Unbroken” from the Country Music Hall of Fame. I also bought the autobiographies of Willie Nelson and Waylon Jennings, as well as the Hank Williams biography by Colin Escott. These were the books the seeded by country music history library.

Having read these books, and even before since I worked in the antiquities market and had seen the common portrayals of Blacks playing banjos at the turn of the Century, it never occurred to me that the banjo was anything but a Black-originated instrument. You will find this in every single country history book. You will not find any source that tells you otherwise.

That said, I respect that Rhiannon Giddens and other may have had different experiences, and the banjo was introduced to them as a White instrument. I shared my theory in the article where that misnomer might have come from. But I continue to be stupefied by people acting like this is something “country music” was responsible for. The historical record on the banjo’s origins are overwhelming and indisputable. I don’t think it’s fair to blame others for your own misunderstanding when the literature is patently clear.

February 16, 2024 @ 5:45 am

Your writing is so bad & one-sided. It’s hilarious & embarrassing. I wish Beyoncé the best. Remember, Trigger—you’re just another lonely guy behind a keyboard with an opinion.

February 16, 2024 @ 9:43 am

ad ho·mi·nem – adjective – (of an argument or reaction) directed against a person rather than the position they are maintaining.

February 22, 2024 @ 1:39 pm

Trigger got triggered…again.

In other news, the grass is green and the sky is blue…

February 25, 2024 @ 4:40 pm

The pale colonizers seems to be more triggered than those with natural color lol I mean… If you pale people going to steal, at least know the history ..so did the banjo came from Europe or you people going deny it came out of West Africa 😂

February 17, 2024 @ 11:40 pm

Boy, you love to miss the point of what Trigger wrote, don’t you?

February 16, 2024 @ 7:07 am

If the masses do not know this history that you seem to think has been profoundly documented, is it because they are lazy or is it because perhaps the story hasn’t been told well enough?

February 16, 2024 @ 9:07 am

What? Lmao that’s a really weak defense. In the words of Fez “crack open a book you lazy son of a bitch.”

February 16, 2024 @ 9:54 am

The influence and importance of Black people to country music has been profoundly documented. This is inarguable, and I feel like I thoroughly explained that in this article. What is also true is there is a disconnect between that knowledge and the general perception by the average American. I also explained that in the article. I think there are numerous reasons for this disconnect.

But to close that gap, what you need to do is educate people. That was the ultimate goal of this article. And the fact that some people are taking it as an attack on their ideology tells you all you need to known about the underlying issues with their ideology where they have perverse incentives to characterize country music in a way that is detached from reality, and that has the byproduct of continuing to erase and downplay country music’s Black legacy, as opposed to propping it up and portraying it accurately.

February 16, 2024 @ 10:40 am

I guess we’ll have to agree to disagree on that history being profoundly documented. If you ask the average country music fan who the pioneers of the genre are, who are they going to list, Trig? Many country fans believe the genre began with Hank Williams, if they even know who that is. If you say that’s because they’re stupid and haven’t read the books that you have or taken the time to learn the Real History, that’s fine.

Just as you believe country music shouldn’t be treated as a monolith (something I find dripping with irony from you, somebody who has a site dedicated to gatekeeping the genre), the people who believe the story of black influence on country music hasn’t been documented WELL ENOUGH are not a monolith either. They’re using this moment, with Beyonce in the zeitgeist, to try and tell that story a little more.

Credit to you for also doing that. I just don’t really care for your approach, which also puts words into people’s mouths.

February 16, 2024 @ 11:45 am

“Many country fans believe the genre began with Hank Williams…”

I agree. And you might be surprised how many of them also know who Tee-Tot is because Hank Jr. has made it a top priority to make sure Tee-Tot’s legacy is cemented in history. When I took some time in 2023 to not rush just through, but really search for the ghosts of Hank Williams in Montgomery, Alabama, this became starkly evident to me.

“the people who believe the story of black influence on country music hasn’t been documented WELL ENOUGH are not a monolith either. They’re using this moment, with Beyonce in the zeitgeist, to try and tell that story a little more.”

I respectfully couldn’t disagree with you more vehemently. I think the exact opposite is what is going on. There is an active and ongoing effort to downplay, if not outright eradicate the Black legacy and influence in country music right now that is historic in nature. That is why I paused everything else in my entire life to get this article published. You are seeing white conservative country fans standing up and saying things like “Charley Pride existed” as they read some of the articles and social media posts coming from these Beyonce surrogates. If you don’t believe me, check out the Facebook comments under this article.

But I appreciate you acknowledging that I am not just wanting to sit back and criticize here. I am trying to be part of the solution. But unfortunately, I don’t have the Beyhive behind me. I have the headwinds of being called a “racist” for daring to say that Black people in country music matter.

It’s an upside down world we live in right now.

February 25, 2024 @ 4:50 pm

You do know the banjo came from West Africa or do pale people try to deny that too lmao karma is going to hit you pale demons so hard. How you steal but don’t know the history behind what you steal. You people have this entertainment to others creativity and then take it as it’s your own. Country music was created by blacks slaves…banjo came from West Africa and the slaves used to play when they weren’t being forced to help you people gain generational wealth and white privilege lol I know my history and I can’t wait for you pale demons to pay

April 1, 2024 @ 7:28 am

White people are the pioneers of the genre. There’s some black influence in country music just like there’s white influence in jazz and hip hop but country music has never been a black genre of music. Blacks can’t claim a genre of music that barely any black people listen to and even fewer participate in. It’s absurd. It would be like whites saying that basketball is a white sport because whites invented it. Nobody today would call basketball a whites sport.

February 16, 2024 @ 6:32 pm

(just FYI, for some reason I can’t reply to your below comment, so I’m going to do it here)

I’ve thought about this a bunch today, and I just don’t think there’s any way we’re going to agree. I also think you make some good points. I appreciate all you do on this site (LOVE the Droptines, btw) and find 70% of my music here. I don’t think your op-eds about country culture (for lack of better term) are for me. They always tend to rub me the wrong way. But you know what? I respect that you write them and spend so much time promoting country music. So I’ll lay down my sword, take the L, and let you get back to the grind of listening to music and spreading the gospel. Appreciate you, man, have a great weekend.

February 16, 2024 @ 7:51 am

Is this serious? Of course country music has erased and denied its black history. Turn on pretty much any country radio station (or popular streaming playlist)–go to pretty much any country concert. These things are as white as a MAGA rally.

February 16, 2024 @ 10:08 am

Did you not read the article?

Saying, “Of course country music has erased and denied its black history.” is an empirically and provably false statement.

“Turn on pretty much any country radio station”

Charley Pride had THIRTY #1 songs on country radio. In more recent times, Kane Brown has had twelve #1’s, Darius Rucker has had eight #1’s, and Jimmie Allen has had three #1s. Is this representation enough? Probably not. But it is there. And by acting like it isn’t, YOU are erasing that Black legacy from country music, not “country music” as a supposed racist institution. It’s country music that awarded these #1s.

“go to pretty much any country concert.”

I was at a country concert last week in fact. Mickey Guyton performed.

“These things are as white as a MAGA rally.”

This is where you are REALLY treading into very ignorant and outdated thinking. First, support for Trump in Black communities is SURGING. This is being well-documented in political reporting.

Second, as I said in the article, if you navigate to social media, you will see folks with “MAGA” in their bios, American Flags and AR-15 emojis telling Black activists and journalists that THEY are the ones erasing the legacy of their heroes like Charley Pride and O.B. McClinton. Throughout this entire thing, I have not seen ONE comment from anyone—not even on Facebook—saying that Black people have no agency or history in country music. On the contrary, they are out here citing statistics to hip-hop reporters who wrote about this issue completely ignorant of the African American influence and accomplishments in country music themselves.

The script has flipped. And if you think that the forces for Black erasure are white conservatives, you couldn’t be more wrong. Blindness to a confused ideology has made Black activists the ones who need country music to have always been White so they can co-opt it for their own devices, and if it doesn’t comply, destroy it.

February 16, 2024 @ 11:12 am

Dude, forget it. These people are never going to think anything other than what they do.

February 17, 2024 @ 11:19 pm

To further your point on why this is happening:

February 16, 2024 @ 10:22 am

go to pretty much any country concert. These things are as white as a MAGA rally.

That’s pretty much true for any blues concert I have been too. And includes folks like B.B. King, Buddy Guy and Robert Cray. And in general, the audience for roots music artists of color are going to be predominantly white. Maybe not so much MAGA. I remember an interview with Rhiannon Giddens where she said that she couldn’t get a gig for her group Our Native Daughters at a historically black college. There wasn’t sufficient interest.

February 18, 2024 @ 12:00 am

That last part makes me glad, as an Afro-Canadian man, that there wasn’t a black radio station playing black music here in Toronto in the ’70’s and ’80’s when I was growing up, especially when seeing the current experiences of this Afro-American couple listening to music they’ve never heard before on their YouTube channel, as well as the experiences of this Latino dude.

February 16, 2024 @ 12:33 pm

“ These things are as white as a MAGA rally.”

Every time I have seen the legendary George Porter Jr. live, it has been a 99.9 percent white audience. I see way more (by a huge margin) of black people at extreme heavy metal concerts I attend. Never been to a MAGA rally, so I can’t speak to that.

February 16, 2024 @ 1:07 pm

“These things are as white as a MAGA rally.”

You are not in touch with reality.

Just parroting the pushed narrative.

Would you like a cracker?

MAGA is multi-cultured, across the board, and financial strata.

NEXT

February 16, 2024 @ 3:55 pm

Just not true. Facts matter. Nothing about MAGA is multi-cultured or economically diverse, although the media typically underestimate their economic class. Just because GOP strategists like Patrick Ruffini are peddling the notion of a multiracial populist MAGA, doesn’t make it true.

“Who are MAGA supporters, and what do they believe in? In these figures, we elaborate on these questions. As the results make clear, they’re not a terribly diverse group: at least 60 percent of them are White, Christian and male. Further, around half are retired, over 65 years of age, and earn at least $50K per year. Finally, roughly 30 percent have at least a college degree. That MAGA supporters are older, Christian, men, more than half of whom are retired, comports with the now-familiar images of the Capitol riots. What may seem a bit surprising is that about half are middle-class by income, and almost 1/3 are middle-class by educational criteria. Apparently, these same images of the riot participants, ones portraying a mainly working-class crowd, were misleading.”

https://sites.uw.edu/magastudy/demographics-group-affinities/

Cults are not usually diverse….

February 16, 2024 @ 6:58 pm

Ah JT, get off, sweetheart. Take a big deep breath.

Your burning drive to impress yourself is going to flame out.

MAGA is not a cult.

However, you are certainly the creature of one.

Took the time to thoughtfully reply to your comment, but Trig doesn’t dare post that response.

February 16, 2024 @ 9:25 pm

and yet this is the POS JT voted for https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qcBQYApjSa4 and remind us again which party started the KKKlan? oh right Democrats , go figure. oh and JT what is it you disliked about Trumps four years in office? the fact he didn’t start a single war? the incredible economy? the fact he made America energy independent for the first time in over 40 years? the foreign wars he shut down? that he made NATO pay their own bills? that he cancelled TPP and created a new trade agreement to preserve America’s sovereignty ? that he passed historic prison reform laws counteracting Bidens racist crime bill from 1993 ? that he put America and not Ukraine first? honestly make me understand why you prefer a career criminal like Biden who has been fleecing his constituents for over 50 years and has an open history of lies, treason and was even just outed by Devin Townsend one of his and Hunters closet friends as a traitor and criminal, over Trump who spent four years genuinely making America better than it had been at any point in your life. if you can’t name specifics and talk like a rational adult and only have temper tantrums and ad hominem cliches, dont waste my time.

February 16, 2024 @ 11:11 pm

Matt and everyone else,

We are not getting into outright Presidential political discussions here that are not adjacent to this article. This is a music website.

Thanks for your understanding.

February 22, 2024 @ 1:43 pm

“This is a music website.”

Of all of the asinine things you’ve wrote on SCM, this is one of them.

February 18, 2024 @ 12:45 am

Matt, you need to get out of this cult, and this man can help you do so: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MhFMgpDi9L8

February 16, 2024 @ 12:31 pm

Trigger, l appreciate you understanding the multiracial understanding of country music’s history. That is important for a critic, you know? But l don’t understand why you would think that just because black influence is written about in a book that the average white man or woman has read it or believes it. But l remember reading Loretta Lynn’s first book when she was threatened that she would lose support for being affectionate with Charley Pride. Thankfully, Loretta kissed him on the cheek and said if she had been “cancelled,” she would have gone home and canned string beans and the heck with ’em all, or something like that. Thank God for Loretta. P.S. l like the Beyonce Texas Hold Em song, and if you think it’s lyrically vapid, it’s at least got humor and that down down part is an excellent hook, country or not. I do think the song is more country than R and B. 😉

February 16, 2024 @ 1:25 pm

I don’t think the average man or woman believe it.

As I said in the article,

“What is true—and can’t be overlooked—is that there is a general prevailing notion in the overall American population that country music is predominantly a genre performed and enjoyed by White people, both in the past and in the present tense. This is due to most country performers being White, though of course there have been exceptions to that rule ever since the very beginnings of the genre.”

All I know to do is to educate people about this. But I have to say, I have been very heartended by the country fans responding to this article with “THANK YOU!” and “Yes!” while I haven’t seen any “No, country music is only White.” I think country fans are more inclined to know about country’s Black legacy and origins than the hip-hop writers who are writing about Beyonce going country because this is THEIR music. They are Charley Pride fans.

Charley Pride won country music’s highest honor, the CMA Entertainer of the Year in 1971. Country music has come a long way from when they were hiding Pride’s photo so radio DJs would play him. BOTH of these things are part of country music’s legacy, and they speak to moments of racial reckoning that should not go erased.

February 16, 2024 @ 7:07 pm

My reference to Loretta Lynn was in fact about the entertainer of the year award that Charley Pride received in 1971 🙂 I appreciate your response and I think it is always good to know and acknowledge that music coming from different influences can make for a powerful “musical meal,” meaning a mix of influences can make for greatness. I appreciate that you want to educate and hope you will continue to do so. For whatever reasons we don’t always understand ourselves, certain words, sounds, rhythms, or combinations of many factors draw us to certain music. If the music is true and real, it will get to us despite ourselves, as I think John Lennon once said. Maybe hip hop writers don’t acknowledge country, Trigger, but my good friend Rose, a black woman friend of mine for many decades, who was raised mostly on “black” music, really likes Chris Stapleton. So, the best we can do is educate each other. For those with an open heart and mind, they will listen.

February 18, 2024 @ 12:36 am

Your liking that Beyonce song shows how (like people who are fans of Taylor Swift) that you know nothing about country or even care about it, and also that you only like a country song if somebody like Beyonce-who isn’t country-is singing it.

Here’s a better example of a country song by women to listen to: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fw7fiWqfpnU

February 25, 2024 @ 4:38 pm

Get a life…do you know where banjos came from? I doubt it…it came from west Africa that was bought by the slaves…so you know country music but don’t know where the instrumental came from…pale people and their racist colonizers mindset

February 25, 2024 @ 5:22 pm

Nobody has every claimed that the banjo was anything but an instrument that originated in Black culture. Nobody. Ever. You won’t find one history book, one documentary, one authoritative source of any origin that has ever said the banjo is a White instrument. Conversely, every single piece of historical literature in country music correctly attributes the banjo to Black origins. Your attempt to use this knowledge as a trump card is not only ineffective, it signals your own previous ignorance on this matter, because anyone even slightly boned up on country music history would already know the banjo is a Black instrument.

Furthermore, the guitar, mandolin, violin/fiddle, bass and cello, piano, and others all have European origins. So the idea that one instrument immediately makes White people colonizers in country music is ludicrous. The steel guitar is Polynesian. That doesn’t make country music Polynesian in total. Similar to the banjo, it lends to the varied origins of the music.

February 16, 2024 @ 6:09 pm

There were also the contributions of Ray Charles, whose recoding company thought he was nuts at the time. And the Pointer Sisters had a brief flirtation with country. About a decade later one of them scored big on a duet with Earl Thomas Conley. Dating back further, does anyone recall “The Boll Weevil Song” by Brook Benton?

February 16, 2024 @ 7:23 pm

Hi Brian-Yes, I definitely remember Boll Weevil by Brook Benton. It’s interesting how then later, Randy Travis, had a number one on the country charts, I think, with “It’s Just a Matter of Time,” which I just read was #1 for 9 weeks on the R & B charts in 1959 for Brook Benton, and number 3 on the pop charts. A great song is a great song, no? And I remember Conway Twitty did “Slow Hand” by the Pointer Sisters and had a hit with it….

February 21, 2024 @ 8:22 pm

“A great song is a great song, no?”

Absolutely. There was quite a bit of cross-pollination of songs, if not performers, even during the ’90s. All-4-One remade John Michael Montgomery’s “I Swear” and “I Can Love You Like That” into pop smashes, Boy Howdy’s “She’d Give Anything” led to Gerald Levert’s “I’d Give Anything,” Mark Wills covered Brian McKnight’s “Back at One.” Even Reba had a moderate country hit with a cover of a Beyonce song (“If I Were a Boy”).

February 22, 2024 @ 2:01 pm

In the summer of 1999, R&B singer Brian McKnight had a song called “Back At One”, which was one of his biggest hits. Mark Wills did a cover of the song later that year and it became a hit for him, too.

Yes, that’s a white country singer doing a cover of a song from a black R&B singer. And in 1999, nobody complained about that.

25 years later, a well-known and highly successful black female R&B singer scores a #1 hit on the country charts, and certain individuals are treating this like it’s the beginning of the apocalypse. SMH…

February 16, 2024 @ 6:55 pm

I am a deeply liberal person and part of a bi-racial family, but have to say that you are 100% right, on this. Though sadly, as we both know… people don’t want to hear the truth. They only want to hear what reinforces their own narrative and viewpoint. There are definitely problems with racism (and misogyny) in country music, but the assertions that Black people exclusively created country music and the attempt to strip away the contributions of White people to the genre is just as egregious and racist as the Whites who fail to acknowledge and recognize the contributions of Black and Brown cultures. This should be something that unites us, but because of the way the narrative is being spun, it will only cause more division and bad blood. It’s a damn shame.

February 17, 2024 @ 1:27 pm

To me its not so much that black people want to be recognized as having an influence on Country music. What they really want is to be seen as the uncontested creators of a genre subsequently colonized by whites. Their goal is not the recognition of blacks as contributors, but blacks as sole creators.

February 17, 2024 @ 4:07 pm

Exactly. And that is detached from the reality of things. As activists have attempted to get more and more traction for their tweets and causes, they have entered into empirically false territory. It stands to reason that 70% of the United States had at least some agency in the formation of some music. It’s indisputable that Black created the blues, jazz, hip-hop, R&B, and the foundations for rock and roll. Along with Black minstrel players and later blues musicians, White immigrants from the British isles took their native instruments such as the guitar, violin, mandolin, and dulcimer, and made old-time music inspired by the folk traditions from where they came from. Saying otherwise is not based in any bit of truth. It’s simply an effort to be hyperbolic to garner a reaction online.

February 17, 2024 @ 11:07 pm

Great article. By that logic all history would be told correctly by the masses. One way to look at it is how schools teach history. If our schools are to be trusted and people grew up believing one thing is correct they normally don’t chose to seek out something else. But if the overall mission is to teach white supremacy then the accomplishments of “others” will be diluted, remixed, or ignored in an effort to meet the mission. So whether it’s critical race theory or the artistic contributions of non whites, it’s nearly impossible to get someone to seek out information contrary to everything they believe to be true. I think that’s why these conversations are necessary. Red or blue pill… someone will always choose the comfort of ignorance.

February 19, 2024 @ 4:41 am

I guess I don’t understand what is so significant about the origin on the banjo.

We are blessed with a broad array of musical instruments in this world. All of them available to artists in any way they choose.

Where’s the trumpet and piano come from and does that matter to musicians who express themselves today on those instruments?

It is exhausting to have folks make controversies and feel slighted over what race of person first conceived of a banjo.

Just stop.

Just play.

February 19, 2024 @ 2:58 pm

I understand your point that the narrative of whitewashing the history of country music may be overblown. But as many others have pointed out, the mainstream average American conceptualization of country is that it is music by and for white people. Which makes it’s Black legacy that much more important and in need of being highlighted.

A couple of other points:

– From your post – “Blacks were synonymous with the banjo, so much so that if White performers wanted to play the banjo, they often did so in blackface to attempt to come across as more authentic.” Seems like you are downplaying the several decades of minstrel and medicine shows that brought the banjo to mainstream white culture. These shows were driven by white supremacist depictions of Black people in order to turn them into entertainment, reinforce ugly stereotypes, dehumanize, show them as inferior, romanticize plantation life, etc. It wasn’t about “authenticity” at all – the shows profited white people as per usual. After the Civil War some Black musicians played in those shows because that was one place they could get work; and at times they wore blackface as well which undermines the authenticity argument even more.

-The Charlie Pride example is a counterfactual in a way but can also be seen as an exception proving the rule. As you point out, naming 2-3 Black country artists is quite a long ways from any sort of true representation. Also it’s worth asking what those artists experienced on their way to some form of tolerance. Charlie Pride’s first songs were sent to radio stations without a photo so nobody would know he was Black. He recounted several racist incidents from fellow country stars and fans (though he chose to not dwell on them). So yes he’s exceptional but he is one part of the broader story.

February 19, 2024 @ 3:53 pm

Hey Life,

Thanks for chiming in.

As I stated in the article, while emphasizing it with “it can’t be stressed enough,” there is definitely a disconnect between country music’s actual history, and the perceived history. I’ve also addressed this in numerous comments, and I agree it’s an issue. That is one of the underlying reasons I wanted to publish an article like this. It was meant to answer the charge that the Black influence had been erased from country, but a byproduct is it also explains that Blacks were in fact a party to country music’s founding.

As for the Blackface portrayals, that’s probably a deeper subject for another time. I wasn’t trying to skim over those details. As I said in the article about the portrayals of Blacks in advertisement and antiquity at that time, it often gave into negative stereotypes, and used the banjo to do that very thing. Maybe “authentic” wasn’t the right word there. My deeper point was in previous eras, the banjo was synonymous with the Black experience, and at some point that got degraded, I’m guessing by cultural iconography in the ’70s.

February 19, 2024 @ 6:04 pm

Thanks for the reply. Wondering what you think about the idea that Charlie Pride was successful in spite of country’s gatekeepers, not because of them. We can look at the Black Country Music Association and Black Opry to learn about the exclusion and racism running through the country music establishment in recent and current times. So it’s not just about history when the powers at be continue actively pushing a “country is for white people by white people” narrative / brand.

March 29, 2024 @ 6:52 am

Greetings ! I am a Black American from South Central, Virginia. Thank you for having the courage to write this article. We need this kind of relevant information available so that we can dispel ignorance and mature in our social evolution. Great job

February 15, 2024 @ 12:56 pm

Also, I have seen a lot of people countering anything said on this issue with talk about how the country charts and the “race” charts were separated at one point, and citing this as sort of country music’s “original sin.” First, that deserves an significant amount of context, primarily that both poor Whites and poor Blacks were segregated onto that chart together at first before being separated by race.

Also, that chart split happened 80 years ago and was later revoked. Charley Pride won the CMA Entertainer of the Year in 1971, and Tracy Chapman just won two CMA Awards. Even if you think that chart segregation decision was racist at that time, why are we holding Garth Brooks and Luke Combs responsible for it, when they weren’t even born at that time?

I will have a deeper article on this at some point because it will take a lot of parsing like this article did. I do think it’s something that needs to be addressed, but I also don’t think it’s the rhetorical slam dunk some believe it is.

February 15, 2024 @ 1:14 pm

If you are talking about me here, I think this is perhaps my fault for not being clear. I don’t hold “country music” as a current institution or genre or whatever responsible for the chart split, and am not trying to blame anyone currently alive for that.

I do think that there is a popular notion, mostly among people that are relatively uninformed about country music, that country music, throughout it’s history, is for white people, by white people. You can see multiple commenters on your Beyonce article expressing that sentiment, and I encounter it fairly regularly (from all demographics!) in my daily existence as a picker. I think a major starting point for that notion was the chart split and marketing thereabouts. T

Apologies if I came off as making a different point, that’s on me. Appreciate your work fostering this discussion.

February 15, 2024 @ 1:28 pm

This wasn’t just a response to you. Ganstagrass literally just tweeted this same chart split point at me. And I’m in no way not saying that it’s an important point. But it in no way justifies statements like, “The greatest lie country music ever told was convincing the world that it is white.” from the Time magazine article. Things happened after that. A dude just commented on Facebook simply “Charley Pride exists.” I think that’s incredibly prophetic and telling where this whole thing has gone. In an attempt to fete Beyonce, they have lost all touch with reality, and White country music fans are the ones stepping up to defend the Black legacy in country music.

February 15, 2024 @ 2:16 pm

Yeah makes sense.

February 15, 2024 @ 2:35 pm

To play devil’s advocate, couldn’t there be less nefarious motives for the chart split? Similar to the chart split that eventually happened with rock. Sure, many of the first generation rock stars were influenced by and sometimes performed country music. But I think we can all agree that there’s no place on country radio for T. Rex. A split was necessary to reflect the separate evolution of both genres.

Likewise, Jimmie Rodgers, Son House, Blind Lemon Jefferson, Dock Boggs, Robert Johnson and the Carter Family were all artists with a rural background, whose music was thematically in line with a rural lifestyle and performed on stringed instruments. You can play them side by side all day. Count Basie and Billie Holiday were phenomenal, but they don’t quite fit in on that playlist the way that Hank Williams would.

February 15, 2024 @ 4:36 pm

The answer is no, and the reasoning is at least two-fold: one) The first separation of rural Southern music into hillbilly and race music was in 1921, which pre-dates (and arguably helped cause) the evolution of country and blues into different genres, and two) We have statements from record executives, song collectors, and field recorders at the time stating that the split was for explicitly racial reasons.

These reasons differed, some being Northern marketing executives not knowing that rural blacks and whites listened to and made the same types of music, some being deliberate attempts to construct a nationalist musical identity, etc.

February 15, 2024 @ 5:41 pm

Thanks for the response. You know a lot more about that particular period of history than I do. I was aware that DeFord Bailey’s records were released to both the “hillbilly” and “race” markets, so it is obvious that record labels helped create the distinction in some way.

I was speaking more to the increasing urbanization of mainstream black music really beginning in the ’30s. The Depression made it less economically viable for record labels to go and locate rural talent and so their attention turned more and more to urban jazz bands, electric blues and finally early R&B and doo-wop. Great music, much of it, but decidedly not country. Some of the old rural blues artists were eventually rediscovered as old men and even Muddy Waters returned to that style for one album, but the mold had already been cast by then. It’s impossible to know what rural audiences (white or black) would have thought about Skip James or Mississippi John Hurt in the ’40s, because they simply weren’t being recorded by anyone. And, hey, the country music industry is probably as much to blame for that as anyone else.

February 16, 2024 @ 6:30 am

Let’s also not forget that “Hillbilly” was used by well-off urbanites at the time in just as derogatory a way as…ahem…that other word. Yes, poor rural whites reclaimed the word in the following decades, but so have black Americans.

February 15, 2024 @ 1:22 pm

There is an active effort to destroy all of country music’s Black history to offer a clean slate for Queen Bey to “reclaim” country music for Black people.

I don’t claim to know but I wonder if this isn’t the desire for many of the people raising this ruckus, to make Beyonce some sort of heroine slaying the dragon of white supremacy in country music. Given Beyonce’s many well-earned achievements this seems unnecessary to me.

Of course it’s the cranky old man in me that sees a lot of our social controversies as attempts by pampered narcissists to create drama where none exists, due to “Selma Envy” (envy of those involved in the Civil Rights Movement) or “Hedgerow Envy” (envy of the “Greatest Generation”). So maybe my cranky bias is coloring my take.

February 15, 2024 @ 1:30 pm

“I wonder if this isn’t the desire for many of the people raising this ruckus, to make Beyonce some sort of heroine slaying the dragon of white supremacy in country music.”

That is exactly what this this is. And for some, this is their moment. This is what they’ve worked or waited for for years. And if it means eradicating every single piece of Black country music history to make that happen, they are more than happy to do it. It’s happening right here, right now.

February 15, 2024 @ 5:12 pm

I think it’s pure silliness. Beyonce will wear her white cowboy hat until it’s time for her to think about Renaissance III. I don’t understand all the arguing about history. The problem isn’t history. The problem is representation now and I sincerely doubt that Beyonce is plotting to be the savior of anything.

Beyonce getting played on country radio and winning country awards isn’t going to make it easier for other artists to break through the country barricades. What she will do, though, is give black artists and musicians the opportunity to work and shine on something big.

February 16, 2024 @ 7:40 pm

I think you are right, Liza, and agree that Beyonce is not trying to be anybody’s savior. If she thinks she is, that is her own personal problem.

I turned 70 recently, and there has always been the crossover stuff in music. Sam Phillips at Sun Records wanted to find a white man with the “Negro sound” so he could make money, and found it in Elvis Presley. Being raised in the 60’s, I remember many white groups who supposedly made blue eyed soul music-Righteous Brothers, Rascals, Mitch Ryder, etc. But you also had Ray Charles in 1962 put out his Modern Sounds in Country Music, which was a big commercial and artistic success. I have a Solomon Burke album and one of his first hits on Atlantic Records, I believe, was a country song, “Just Out of Reach (of My Two Empty Arms.)” So, cool it people, and enjoy the music. Thanks for your comments.

February 21, 2024 @ 11:29 am

was Mitch Ryder white?

February 21, 2024 @ 11:30 am

was Mitch Ryder white.?

April 2, 2024 @ 5:44 am

This is stupifying….I’m kind of in shock reading this article. I’ll have to sit down with my computer and write a longer, more thorough response – but wow. All I will say at this point is yes, I too look askance at the new mythology being born in from of our eyes, but your central thesis is equally overwrought. Yes there is a segment out there using this moment in ways I’m uncomfortable with, but man, you cannot erase my experience, nor the experience of so many like me. Tony Thomas started black banjo players then and now list serve because he kept getting flamed on Banjo-L for daring to say the banjo began as a black instrument. You don’t know what the CCD went through, nor I, nor Rissi Palmer. Anyway I’m on my phone and can’t accurately respond to you – I don’t actually disagree with some of your points. I’m one of the few tooting the horn of the ‘cross-cultural creation’ of all of our earliest music. But the fact that you read some books that say the banjo has black origins- and yep, they are out there, it’s great- the scholarship has been out there since Dena Epstein and earlier – and think that solves the matter as to what regular-ass people know…just, wow.

April 2, 2024 @ 11:20 am

Hey Rhiannon,

Thanks for piping up.

Since writing this article three weeks ago, and since delving deeper into this Beyonce moment, what I have come to understand is that the Black community and the White community are fundamentally having two different experiences based off of preconceived notions about country music, and the role of Black creators in it. The last thing I want to do is erase anyone’s experience. I think for White country fans, they know about Charley Pride, they know about Ray Charles, they know about more contemporary artists such as Charley Crockett or Kane Brown, and so they bristle whenever anyone says Black people are not welcomed in the genre, or the Black legacy has been erased. When people tell them that Black minstrel players and blues artists were foundation to the genre, and the banjo is a Black instrument, they go, “Makes sense,” whether they knew it before, or not.

Meanwhile, Black people have always felt alienated and in a place apart from the country music legacy. This is the fault of country music not being expressive enough that Black fans and creators not only belong, but are a part of the country music story. That’s different from being erased from the physical written history, but that public perception is real, and manifests in real world attitudes and perspectives. So when someone says, “The banjo is a Black instrument,” many Black people don’t react, “Makes sense.” It’s an epiphany, a revelation, an awakening, just like learning of the foundational Black contributions to country at large.

This is where the big disconnect is happening. It’s also where the release of this Beyonce album can help bridge that gap in understanding, and help enlighten everyone’s perspectives.

That said, if Taylor Crumpton and others get their way of pushing narratives like, “Country music has always been Black music, and country music has never been white music,” it could only create deeper rifts in the culture war and misunderstanding that will be harder to heal than the rifts that already exist.

Before I wrote this article, I wrote to Taylor Crumpton, and asked her who ever said that country music was only white music. I crowdsourced for information on who ever said the banjo was a white instrument. I am not saying those moments and quotes don’t exist. I want to find them so I can speak to them, and potentially correct and dismiss them. But as someone who has read history book after history book, I have yet to discover these assertions myself. I’m not omniscient so I can swear this Black erasure in the written history is not out there. But if it is, it is much harder to come by compared to the literature that says otherwise.

But again, either way, the public perception is different. That is one of the reasons I wanted to pull the literature off the shelf, cite examples, give specific quotes, and let EVERYONE know, yes, Black people are a part of country’s history, and there’s not even any dispute over it. It’s right here in the most important works on country history that you can find.

April 2, 2024 @ 11:33 am

I hear you. I’ve never said it’s not in the history books. I’ve even said the folks we talk about, like the Hank Williams’s, and the Bill Monroes, freely acknowledge the black musicians who inspired or taught them – for me it’s the popular narrative about these people that leave their teachers out. I can only speak from my experience, and the countless folks I have played for, taught, lectured to, and spoke to after the show – this is NOT common knowledge. I’m sorry to break it to you, but most people don’t reach research books about popular music. And how music is sold and how it is categorized is very much tied to race, and that’s all up in the literature too. You try to be a black banjo player and deal with YEARS of being questioned because your audience assumes that the banjo is invented by white mountaineers. I ain’t making that shit up, I promise you. All that being said, I think there is a larger conversation here for those of us able to engage in open conversation with a willingness for dialogue, potential disagreement, and hopefully, common growth. But it takes being able to see past your own experience. I have my own, but trust me, I have heard from so many others with the same.

April 2, 2024 @ 11:51 am

Definitely agree that written history and public perception are two completely different things, and there is clearly a gap when it comes to the Black legacy in country music. I tried to emphasize this in the article itself, but perhaps could have done a better job of clarifying that. But all I know to do to challenge those public perceptions is to publish articles like this and try to highlight how important the Black legacy is to the foundations of country music, and to point out where this is chronicled. I think the fact that it actually is in most major country history works is good news. This makes the job of changing the public perception infinitely easier since we don’t have to re-instill it in the historical record, we just have to re-empahsize it.

The Ken Burns “Country Music” documentary had 34.5 MILLION unique viewers. That’s a lot of folks. And I think Ken Burns did a good job making sure Black creators were given credit for their important contributions. We just have to recognize that this work needs to be ongoing, and to continue to talk about it until that public perception aligns with the truth of country history.

February 15, 2024 @ 1:32 pm

I dont understand why any of this matters. If you like Beyonce, good. If you dont, also good. Just go to the next song. Switch the station. Whatever. I never listen to the radio, so I dont care who they play, dont play, etc. I listen to what I want, when I want. That’s the beauty of the age we live in. Music on demand at your fingertips.

There is so much music out there that it is almost impossible to listen to everything…of any genre.

To make this much fuss over Beyonce, whichever way you lean, is a bunch of nonsense.

February 15, 2024 @ 1:58 pm

It’s because we live in a country where we overall have it good enough for people to have the luxury of being upset over stupid, asinine, often fabricated things just to feel important (obviously this isn’t me saying that we aren’t facing real and serious problems in our country.)

February 15, 2024 @ 1:42 pm

Trigger, I misspoke in the comments of another article a week or so back. In relation to Tracy Chapman being the first black woman to pen a #1 country hit, I went looking for the first black man to do so and landed on Otis Blackwell, who wrote two #1s for Elvis Presley and one for Jerry Lee Lewis back in the ’50s. Blackwell was a great songwriter and deserves to have his name out there, but I researched it more and that distinction isn’t his. Noted blues artist Louis Jordan hit the #1 spot on the country charts twice in 1943 and 1944 with two self-penned songs. And there may have been others before him and around the same time.

In addition to the songs by Blackwell and Jordan, I will reiterate that “She’s All I Got” was a major hit for Johnny Paycheck and a contender for the CMA’s Song of the Year. It was written by Gary U.S. Bonds and Jerry Williams, Jr. (Swamp Dogg), both notable R&B artists in their own right. They’re both still alive, so maybe Time can reach out to them and ask their opinion on the royalty checks they’ve been getting for over 50 years.

I do agree that these people are the ones erasing country music’s black history, particularly in discounting Charley Pride and the pioneering work of DeFord Bailey. But since this discussion seems to be around black women in particular, Linda Martell had two top 40 country singles in 1969, the Pointer Sisters had one in 1974 and Anita Pointer hit #2 in 1986 in a duet with Earl Thomas Conley. Black female songwriter Alice Randall had a hand in writing a #1 hit in 1994 and, if that seems late, it’s important to remember that female songwriters weren’t really the norm in any genre much earlier than that, singer-songwriters like Loretta and Dolly aside.

That doesn’t mean that there aren’t dark corners of country music’s past. But same can be said for every other genre.

As far as Beyonce goes, what I’ve heard is no worse than anything else getting country airplay these days, and, unfortunately, no better.

February 15, 2024 @ 2:10 pm

A few years ago, I was watching some country awards show with my daughter and Mickey Guyton performed. She said “doesn’t that lady know black people don’t sing country music?” I said, “They most certainly do ” She said, “name 5 – and don’t count Hootie.”

I came up with Jimmie Allen, Charlie Pride, and stretched to Ray Charles. I knew there were many more, but I couldn’t think of one to save my life.

So, after the show was over, she and went to Google and researched it was a wonderful learning experience for us both.

I said all that to say this – maybe we can use this as a “teachable” moment.

Yes, Beyonce’s most ardent supporters are going to frame this as her smashing down the barriers to black artists in country music. But maybe, just maybe those who have less allegiance to her can be reached with the truth.

Of course, maybe I am just being a big ‘ol Pollyanna wearing rose colored glasses.

February 15, 2024 @ 4:49 pm

Cleve Francis, O.B. McClinton, Stoney Edwards, Big Al Downing and Trini Triggs are five more. The Pointer Sisters won a country Grammy for “Fairytale” – a good country single.

February 15, 2024 @ 6:04 pm

Boy ya talk about real country performed by Big Al Downing. He was one of my favorite country artists . I’ll tell ya he had the best back up band I’ve ever heard in my life. Because of Big Al I’ve been a country fan since. I’ve sat and watched all this drama.

To much bs on a biscuit will ruin the batch ! Taylor.,,Beyonce’.. It’s always been how country makes me feel that brings me coming back. I’m gonna just say hey to hell with genre bs. Music is music is music. Red yellow white or black we are all precious in His sight !!!

February 15, 2024 @ 6:59 pm

I would hear Big Al in heavy rotation on 1050 WHN out of New York. He got a date on Hee Haw when that was a meaningful thing. Big Al was a good artist.

February 16, 2024 @ 2:27 am

@Todd P– The problem is that your list ony reinforces the idea that black artists were not welcome in country music. Big Al Downing had 15 singles in the late ’70s-’80s. The biggest two made it to #18 and #20. Only three others cracked the top 40. O.B. McClintonhad about 15 singles that charted–the highest two made it all the way to #36 and #37. Only one other made the top 60!.

The great Stoney Edwards, who was rediscovered in the CD era (after his death) had something like 20 singles on Capitol in the 1970s. Two of them went to #20. The next highest made it to #39. And Dr. Cleve put out 8 singles on Capitol Nashville (then called Liberty, for a while) in the ’90s. Only four charted at all, the highest one making it to #47.

February 16, 2024 @ 9:05 pm

I understand your point. These artists were talented people who, for whatever reasons, ended up at the fringes of industry. Big Al had some success in other genres which proved he had a lot of talent.

There aren’t a lot of top-tier black artists in country just as there aren’t a lot of white artists who thrived on the R&B charts. There’s blue-eyed soul with Boz Scaggs, Bobby Caldwell and the like who have that niche to work in.

What I couldn’t tell you is how much pressure is there in the (I don’t like this description) Black community for Black artists not to like or perform country music.

I’m a big Don Williams fan. On Facebook, there are Don Williams fan communities chock full of cell phone videos of Don Williams fans in Africa performing his songs. Don has as broad a fan base as anyone in the world in this genre.

If the music is genuine and heartfelt, it will touch people. That’s what I see is at the heart of this site. From Gabe Lee to Brennan Leigh and beyond, if it’s sincere and the artist has talent, you don’t need a formula for good music. It’s a question of getting the music out to people. The interwebs have given us the means to hear it and share it.

February 15, 2024 @ 2:18 pm

I wish I were intelligent enough about the history of country music to add something meaningful to this, but there are others on here that are and will. I do believe this is an important discussion, because it has triggered Trigger. And one thing I believe is that he doesn’t blow stuff up for no good reason. So dismissing all of this as simply, why should I care because I’ll listen to what I’ll listen to is a bit short sighted.

I love independent country music and I’ll tell anyone who will listen as much. At the end of the day, it’s still country music and falls under the umbrella. So the last thing I need is someone who believes all of this bullshit flying around social media judging me and assuming my musical choices imply an intolerance or racism. I don’t need country music to be labeled as racist simply because I don’t want my appreciation for it to represent anything other than that – a love of the MUSIC. I do think what you’ve written here is important Trigger and I do hope it reaches the people it needs to reach.

February 15, 2024 @ 2:23 pm

All of this whining feels like compensation or cope for the music itself not being that good. If she releases a badass, heartfelt, actual country album, I’ll buy It and she will gain my respect. I think it would be a huge hit. There wasn’t anything to stop that half a century ago with Pride, and there’s nothing to stop that now. Other than the music itself. But therein lies the problem, and the reason for all this noise.

February 15, 2024 @ 2:50 pm

What a great article. Most of those books are fantastic reading.

I guess my question to anyone who cares to answer it, what does any of this mean?

A decade ago people were freaking out because country concerts became booze fests

Party down south was on TV and had people pissing on each other

The Florida Georgia Line guys were making